Edition created by Jocelyn Zheng

Table of contents

- Introduction

- “The Heart’s Memory” by Catulle Mendès

- Interpretive Essay

- Creative Response

- References

- License

Introduction

Editor’s Note

I came across this story in my search to find a fairy tale that had fallen into obscurity. My motivation comes from my interest in writing fantasy stories, which contain elements often inspired by fairy tales. The writing community online maintains their presence through blogs and personal websites, and I discovered a website by Sarah Beth Durst, where she explains that her reason for exploring obscure fairy tales is to find inspiration in their unique elements for her own creative writing. “The Heart’s Memory” is unique in that it features the heavy theme of grief, and the magical element of distorting paintings — although this turns out not to be as it seems. Another motivating factor for me is my desire to read a fairy tale that is unlike those that are mainstream in the modern world, such as The Little Mermaid and Sleeping Beauty. Unlike those stories, this one is surprisingly not meant for an audience of children, as one would expect with a fairy tale, although it retains the accessible, easy to read language and lighter themes — at least on the surface — that are common in fairy tales. My hope is that by presenting this fairy tale as a picture book, making reading a more enjoyable experience for even people averse to it, I can bring a new story to the eyes of authors and a wide range of interested or curious readers alike, and broaden their idea of what is possible within the fairy tale genre.

For this editorial, I began by finding material detailing the publication context and author background in order to gain insight into historical context that might have influenced this story, and then searching for scholarship on the purpose and types of fairy tales in order to classify this story. I experienced many challenges, one of which included being unable to explore the author’s background due to a lack of materials about the author. In addition, the fact that many of the author’s other related works existed only in French posed a language barrier to me. I eventually discovered an anthology in which some of Catulle Mendès’ fairy tales were featured in English. I also attempted to locate the original French version of the story to better understand choices behind specific words and phrases, but was unable to find it online.

Publication Context

The English translation of “The Heart’s Memory” was published by The Clarke Company in London in The Universal Anthology: A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Mediaeval and Modern, with Biographical and Explanatory Notes, Volume 32, in 1899. It was published along with four other fairy tales by Catulle Mendès under the collection name “Spinning-Wheel Stories”. The series contains a total of 33 volumes, and a limited number of sets were printed. The editors of “The Universal Anthology” were Alois Brandl, Léon Vallée, and Richard Garnett, the last of whom was a British librarian at the British Museum, who lived from 1835 to 1906 and translated, compiled, discovered, and edited an extensive number of works. The Garnett family “exerted a formative influence on the development of modern British writing”, as stated by Encyclopedia Britannica.

The original story was in French, titled “La mémoire du cœur”.

About the Author and Historical Context

Catulle Mendès, a French poet, playwright, and novelist, lived from 1841 to 1909. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, he was a Parnassian: a member of a group of French poets who emphasized “objectivity, technical perfection, and precise description” in reaction to Romantic “emotionalism”. In typical Parnassian style, his writing captures attention through tone and extreme moral situations while masterfully employing literary techniques.

France’s nineteenth century was tumultuous: it was a period “marked by perpetual revolution and regime change”, industrial growth, and reforms, according to Fairy Tales for the Disillusioned: Enchanted Stories from the French Decadent Tradition. Cultural, artistic, and intellectual movements arose in response, which led to the appearance of fairy tales during this time. In general, fairy tales in France, referred to as the genre conte de fées, often appeared during times of societal change or political turbulence. During the nineteenth century, “the genre took on new life through rewritings and new tales” by authors such as the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, and George Sand. However, the nineteenth century was also an age of technological advancement and empiricism, and “witnessed the development of science fiction as a genre”, which threatened to render this French genre of lighthearted innocence obsolete, something that Mendès himself realized. His other fairy tales, including “Dreaming Beauty” and “The Last Fairy”, featured themes of fairies and belief in magic to counter this rationalism that he detested, although with the additional cynical twist that he often rejected a happy ending, a deviation that modern readers will recognize from the common fairy-tale ending. For example, the girl in “The Last Fairy” chooses not to save the last fairy, and Sleeping Beauty rejects the prince who comes to save her in favor of continuing her century-long dream in Mendès’ rendition called “Dreaming Beauty”. In comparison, “The Heart’s Memory” refers to fairies only in passing and hints at the possibility of magic, although perspective makes subjective the matter of whether the story ends happily or not.

Classifying the Story

In “A Study of Fairy Tales”, Laura Fry Kready elegantly summarizes the purpose and value of fairy tales: “All children are poets, and fairy tales are the poetic recording of the facts of life.” Thus, the purpose of fairy tales is to gently expose children to the nuanced world while capturing and entertaining their imagination. “The Heart’s Memory”, however, only seems to serve this purpose on the surface level by merely possessing the basic elements of fairy tales. The aspects of fairy tales that the story demonstrates, which are detailed in “A Study of Fairy Tales”, are the qualities of surprise and mystery, appeal to the senses through vivid imagery, emphasis on beauty, and use of humor. In addition, like many fairy tales, “The Heart’s Memory” remains largely removed from time and place by ambiguously referring to its setting as “a kingdom”, and refraining from offering specific historical details. The story deviates from typical fairy tales on the quality of leaving the reader with emotional or moral satisfaction, which is enhanced by Mendès’ decision to convey the dark themes of the story in a format typically meant for children, creating an unsettling effect. Further analysis of this effect is included in the interpretive essay.

About the Transcription

In the transcription of the text, I have removed spacing between punctuation that may be confusing to a modern English reader. I have also fixed inconsistent capitalizations throughout the text to be consistent with modern convention. I leave the word choice and grammar as is in order to preserve the tone and style of writing of the story, as well as descriptive phrases and words such as “somber” and “rosy” which are important to the plot. I have also kept the Roman numerals separating each subchapter of the text, which divide the story into its exposition, rising action, and climax. The use of Roman numerals in this manner was also demonstrated in another one of Mendès’ fairy tales: “Isolina/Isolin”.

“The Heart’s Memory” by Catulle Mendès

I.

The kingdom was in affliction because the young king, since he had become a widower, paid no more attention whatever to affairs of state, but passed his days and nights in weeping before a portrait of his dear lost one.

This portrait he had painted himself of old, having learned to paint on purpose; for there is nothing more cruel to a lover or a truly enraptured husband than leaving to another the task of reproducing the beauty of his beloved: artists have a way of gazing at their models close to, which could not please a jealous person; they do not put on the canvas all they have seen; something must be held back in their eyes, and in their hearts as well. And this portrait was now the young king’s only solace; he could not restrain his tears in contemplating it, but he would not have exchanged the bitterness of those tears for the sweetness of the happiest smiles. In vain did his ministers come and tell him, “Sire, we have received disquieting news: the new king of Ormuz1 is raising an innumerable army to invade your states;” he pretended not to hear, his gaze ever fixed on the adored image.

One day he fell into a great wrath and nearly killed one of his chamberlains, for hazarding the hint that the most legitimate sorrows ought not to be eternal, and that his master would do well to think of marrying some young maiden — emperor’s niece or peasant’s daughter, it mattered not. “Monster!” cried the inconsolable widower, “how dare you give such dastardly counsel! Would you have me unfaithful to the most lovable of queens? Take yourself out of my sight, or you shall perish by my own hand. But before you go, understand and repeat it to every one, that never shall a woman sit on my throne or sleep in my bed, unless she is in every point like her I have lost!”

And he knew very well that in speaking thus he pledged himself to almost nothing. Such as she lived again in her golden frame — dead, alas! For all that — the queen was so perfectly beautiful that in all the earth one could not find her peer. Brunette, with long soft hair that flowed like liquid ebony, forehead rather high and of amber-tinted ivory, eyes of the depth and blackness of night, mouth well opened by a smile where all her teeth glittered — she defied comparisons and resemblances; and even a princess who had received in her cradle the most precious gifts of all the good fairies2 could not have had such beautiful somber hair, such deep dark eyes, nor that forehead, nor that mouth.

II.

Many months passed by — more than a year — without bringing any happy alteration in the gloomy state of affairs. News more and more alarming was received from Ormuz: the king deigned not to have any care for the growing peril. It is true that the ministers collected the taxes in his name; but as they kept the money in place of employing it to equip soldiers, the country did not escape being ravaged, after having paid not to be so. So every day before the palace there were groups of people, who came to petition and complain. The lover of the dead woman did not rise out of his melancholy; he had no attention save for the silent charm of the portrait.

Once, nevertheless — it was the hour when the dawn tinges the glazings with rose and blue — he turned toward the casement3 to listen to a song that went by, a thin shrill song, sweet and matinal4 as the carol of a lark. He took a few steps in surprise, glued his face to the pane, and looked out. He could hardly restrain a cry of delight! He had never seen anything so charming as this young shepherdess leading her flock of sheep afield5. She was blond to such a degree that her hair gilded the sun rather than was gilded by it. She had a rather low forehead, rosy like young roses; clear eyes, of the clearness of dawn; and her laughing mouth was so tight that even when opened for the song she showed barely five or six little pearls.

But the king, thoroughly charmed as he was, tore himself away from the sight, putting his hands over his closed eyes; and, ashamed of having for a moment turned away from the lovely deceased, he came back to the portrait, and knelt there weeping with sorrow and joy: he remembered no longer in any way that a shepherd maid had passed beneath the window, singing. “Ah! You may be quite sure,” he groaned, “that my heart in mourning belongs to you forever, since there exists no woman that resembles you; and for me to constitute a queen would require that from a mirror where it should be immortalized, your image should come forth alive!”

III.

Now on the next morning, while admiring the portrait of the dead woman, he had a painful surprise. He said to himself : “There is something very strange here. I shall have to believe this hall is damp; the air that is breathed here is not good for paintings. For really, I remember perfectly that my queen’s hair was not as dark as I see it here. No, surely, it had not that blackness of liquid ebony. It was sunny here and there, I remember — the color of dawn, not of evening.”

He called for his brushes and his palette, and very quickly corrected the portrait which the damp air had spoiled. “All right now! Here is really the light golden head which I loved so passionately, which I shall always love.” And full of a bitter pleasure, he renewed, on his knees before the image now just like the dear model, his oaths of eternal constancy.

But in truth, some malicious spirit must have been playing tricks on him; three days gone by, he was compelled to acknowledge that the portrait had once more undergone notable deteriorations. What did that mean? Why was this forehead of amber-tinted ivory so high? He had a good memory, thank God6! And he was sure the queen had a small forehead, ruddy7 and fresh like young eglantines8. With a few touches of the brush he lowered the golden hair in front, and made the forehead rosy — a clear rose. And he felt his heart full of an infinite tenderness for the restored picture.

The following day it was worse yet! It was evident that the eyes and mouth of the portrait had come to be changed by a mysterious will or by some accident. The beloved object had never had those somber pupils, of the blackness of night, nor that too much opened mouth, which showed nearly all the teeth. Oh, quite the contrary! The morning blue of the sky, where quivers the carol of the lark, could not equal in softness the azure of the eyes with which she regarded her lover; and as to what had been her mouth, it was so tight that even when opened for a song or a kiss, she showed barely a few dainty pearls.

The young king felt himself seized with a violent wrath against that absurd portrait, which contradicted all his cherished memories! If he had had in his power the execrable enchanter to whom this transformation was due — for to a certainty there was some enchantment here — he would have avenged himself on him in terrible fashion. For a while he could have torn it down and trampled it under foot, that lying image! He calmed down, however, thinking the mischief was reparable. He set to work; he repainted it according to his faithful memories: and a few hours later, there was on the canvas a young woman with eyes of blue like the far-off dawn, and mouth so small that had it been a flower it could have barely held two or three drops of dew. And he gazed on his queen, full of a mournful rapture. “It is she! Ah! It is indeed herself!” he sighed.

And so he had no objection to make, the day when the chamberlain — who was in the habit of looking through keyholes — advised him to take for a wife a dainty little shepherdess who passed every morning before the palace, singing a song; for she resembled in every point — a little handsomer, perhaps — the portrait of the beautiful queen.

Interpretive Essay

In this expository essay, I analyze the literary techniques and writing style that Mendès utilizes in characterization and plot to craft the theme of impermanence of the heart’s memory.

The characterization of the king is constructed through his actions, dialogue, and beliefs. Throughout the story, the king engages in actions that prove the extreme level of obsessiveness to which he clings to his deceased wife. As the story progresses, this becomes a point of irony; he starts to believe that his wife looked like the shepherdess, even repeating the exact words he used to describe each of them at first. His obsession also manifests in the way he neglects his kingdom, nearly killed his chamberlain for suggesting that he move on, and continuously alters the painting, even delusionally finding relief in his “good memory.” These drastic actions serve as a humorous element that gives the story a lighthearted quality and keeps the reader engaged while highlighting the nature of the human heart to forget, even in the face of heavy subjects such as obsession and grief.

After seeing the shepherdess, the king begins to forget what his deceased wife looked like, believing that she really looked like the shepherdess as he overwrites the painting’s features with that of the shepherdess. From this, it is clear that the king has overcome his grief for his wife without realizing it, but is in denial. The chamberlain then serves as a voice reason and the key to revealing that the king has moved on, as he literally peers “through keyholes” to discover that the king has been painting the shepherdess.

Throughout the story, Mendès employs a writing style in which the narrator often has exclamations of emotion to guide the reader’s reactions and feelings in response to the king’s actions. This act of the narrator verbalizing things that the main character may be saying or thinking is termed free indirect discourse, which Mendès utilizes in a very expressive style. For example, the narrator’s commentary on the king’s mental state during grief at the beginning of the story includes an exclamation of “dead, alas!” in reference to the late wife. Later, when the king sees the shepherdess, the narrator exclaims, “He could hardly restrain a cry of delight!”, conveying the extent of the impact that the shepherdess had on the king. As the painting first begins to change in the king’s mind, the narrator satirically comments: “He had a good memory, thank God!” Finally, as the king grows increasingly distraught, the narrator’s exclamations, one of which includes “that lying image!”, also increase in number to reflect this. Therefore, these exclamations shape the view of the king in the reader’s mind, and bring to attention the changes in the king’s character throughout the story.

Mendès utilizes ekphrasis, a vivid description of a scene or visual work of art, in describing the changes in the painting and reuses his specific choices of words in order to effectively portray reality despite the delusional king’s beliefs and actions. In particular, the descriptions of the deceased wife and shepherdess are essential to clearly understanding the plot of the story. The king’s late wife is described as “somber”, having “eyes of depth and the blackness of night”, hair like “liquid ebony”, with a “forehead rather high” and a largely “opened mouth” — imagery that is evocative of night and darkness. The shepherdess, contrastingly, is depicted using words such as “blond”, “rosy”, and possessing a “tight mouth” and “blue” eyes with “the clearness of dawn”. These strikingly different and vivid descriptions allow readers to easily distinguish the two characters and recognize what is really happening when the king believes that supernatural forces are at play when the painting seems to change. These descriptions give a more pessimistic impression of the deceased wife than the shepherdess so that one may feel relief by the end of the story, when the king leaves the woman who represents shadowy uncertainty in favor of the woman who represents bright clarity. Mendès uses the king’s old and new wives as metaphors for overcoming grief, which starts with darkness until one is able to escape into the light. It calls to mind the phrase “each day is a new beginning”, as the king is shown to move on from his grief by the end of the story. This also conveys the idea that this act of moving on is as inevitable as the passage of time from night to morning.

Even further below the surface of “The Heart’s Memory” is an underlying cynicism that is portrayed through the king’s reactions and enhanced by the genre of the story. After the king’s deep loyalty to his late wife is established at the beginning of the story, upon seeing the shepherdess, the king weeps “with sorrow and joy”, two contradictory emotions that foreshadow the king’s contradiction to his avowed loyalty. We are then explicitly told that he “remembered no longer in any way” the shepherdess, though in actuality, his late wife was the one he forgot. The narrator’s satirical remarks about the king emphasize his increasingly conflicting actions, especially with the final line of the story: “for she resembled in every point — a little handsomer, perhaps — the portrait of the beautiful queen.” The king has not actually moved on from his grief at all. At the end of the story, the king does not become a character that the reader can empathize with and root for due to his abandonment of his initial ideals, and that he is still in denial at the end. This type of ending is unlike that of other fairy tales such as “The Little Mermaid” by Hans Christian Andersen. In “The Little Mermaid”, the mermaid’s fate is put into the hands of the child reader as the story concludes: when she “sees a naughty or wicked child”, this “add[s] to [her] time of trial”. This ending is effective since the reader is motivated by hearing about the mermaid’s story to help her. With “The Heart’s Memory”, however, a sense of perverseness underlies the king’s situation by the fact that the story, intended for adult readers, is being told through the childish medium of a fairy tale. This disturbing quality underscores the cynical tendency of the heart not to really forget, but to do so in a way that instead enforces deep denial.

Creative Response

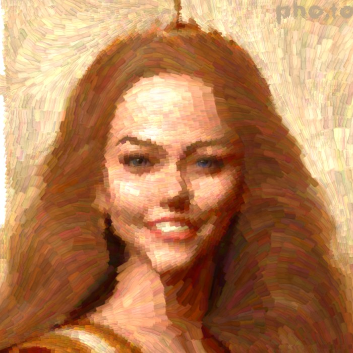

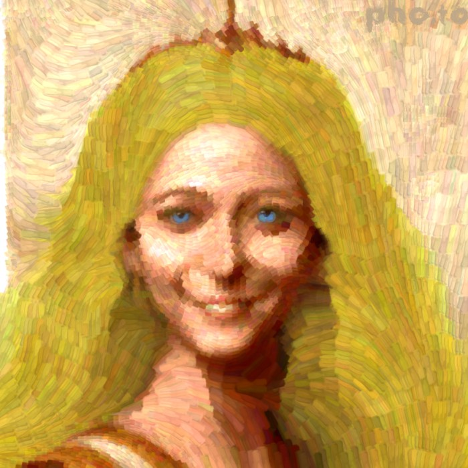

For this story, I thought it would be fitting to create paintings depicting each scene, since a painting is the central object of the story. To enhance the experience of reading this story, I decided on a picture book format in accordance with the fairy tale genre. Due to a time constraint, I could not illustrate each picture from scratch; instead, I utilized Microsoft Copilot’s text-to-image capabilities to generate images based on prompts. I then used Fotor to apply the style transfer technique on these images, using two painters’ art styles, to better portray the setting of the story and unify the diverse AI-generated images by forcing them to employ the same color schemes and texture. This also allowed me to control the progression of the story: for instance, changes in saturation, brightness, and color from subdued, darker hues to cheerful, brighter ones parallel shifts in tone and to the plotline.

I encountered many challenges throughout this task. First was the difficulty in generating consistent images: despite my detailed prompts that clearly stated the elements to include in the image, the resulting images often missed important attributes or added unwanted features. I decided to forgo handling multiple complex elements within each image, and instead have each image feature one action or subject. For example, the first image features the king’s suffering, but cannot also depict the painting that he is supposed to be weeping in front of. However, it was still difficult to accurately capture the king’s emotions in the generated images: in the second image, the depth of the king’s obsession is not reflected in his gaze or body language. The king’s age also fluctuated between scenes, despite my attempts to specify it clearly, so I resolved this by attempting to hide it behind the style transfer filters that I applied after generating the images. Another challenge was generating a painting for the king’s wife; after many failed attempts to change small features of an image, I resolved to start with one generated image, and then gradually photoshop the rest using Procreate so that each subsequent image depicted different stages of transformation from the original image. I then applied a different van Gogh style filter to these images, to differentiate them from the rest of the images in the picture book.

The images I generated for the book are inspired by the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) at first, and transition to the style of French painter Claude Monet (1840–1926), which I chose to be in accordance with changes in the plot. Both painters lived during the time that “The Heart’s Memory” was written and published, although van Gogh’s life ended prematurely and his work was only recognized posthumously — just as the king’s wife in “The Heart’s Memory” died early, and the whole story takes place after her death — while Monet’s paintings were very successful during his lifetime. van Gogh’s paintings feature many nighttime scenes, such as those of The Starry Night (1889), Café Terrace at Night (1888), The Church at Auvers (1890), and Wheatfield with Crows (1890). They tend to portray more somber themes, as depicted in Prisoners Exercising (1890) and Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (1886). The word ‘somber’ is used notably in “The Heart’s Memory” to describe the portrait of the king’s late wife, whose facial features evoke themes of darkness and night. On the other hand, Monet’s paintings feature soft, saturated, and often brighter colors in an effort to create images that accurately reflect nature as he perceived it during the daytime, such as in The Water Lily Pond (1899) and The Artist’s Garden at Giverny (1900). The king in the story shares this desire to precisely capture natural beauty, even going so far as to learn how to paint. It is the reason that he so desperately and unrelentingly ‘fixes’ the painting of his wife over and over, attempting to make it accurately reflect his memories. The shepherdess that he ends up painting is described with words that evoke dawn and morning. In this way, the king’s deceased wife and the shepherdess stand in stark contrast with each other, as do the paintings of van Gogh and Monet.

Another reason I chose these painters was for the fittingness of the beliefs that their art was built upon. The predominantly French art movements that these painters were a part of explain the unique style and techniques employed in their artworks; Monet was an Impressionist painter, and van Gogh was a Post-Impressionist painter. Impressionism was characterized by the effort to precisely depict changes in light and passage of time, and also placed emphasis on the importance of movement as a fundamental aspect of the human experience. Post-Impressionism was defined by its rejection of the limitations of Impressionism: where Impressionism attempts to stay true to the natural orientations of light and color, Post-Impressionism seeks to utilize abstraction, distortions, and unnatural colors to emphasize expressiveness. These ideas echo the themes of the story — in attempting to precisely capture the visage of his deceased wife and maintain it unchangingly throughout the passage of time, the king inadvertently allows himself to distort it, expressing and revealing the true fickleness behind his emotions. My reason for choosing painting styles to use in the images goes beyond the paralleling presence of a painting as a major plot point in the story: just as memories and feelings are constantly in flux, so is the state of art. Art movements embody this instability: the methods and trends by which art is created change with time. Finally, the story seems to deliver a message on the importance of moving on in life, an idea shared by the Impressionist emphasis on movement as a fundamental aspect of the human experience.

References

Brandl, Alois, et al. The Universal Anthology: A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient Mediaeval and Modern, with Biographical and Explanatory Notes. Clarke Co., 1899, Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=90tOcviPxdUC&oe=UTF-8, Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Catulle Mendès”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Catulle-Mendes. Accessed 4 April 2024.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Parnassian”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 Nov. 2010, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parnassian. Accessed 4 April 2024.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Richard Garnett”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Richard-Garnett. Accessed 4 April 2024.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Vincent van Gogh”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Apr. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Vincent-van-Gogh. Accessed 4 April 2024.

Durst, Sarah Beth. “Obscure Fairy Tales.” Sarah Beth Durst, 2023, www.sarahbethdurst.com/fairytales.htm.

Kready, Laura Fry. A Study of Fairy Tales. Houghton Mifflin, 1916, Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=NW0AAAAAMAAJ&dq=19th+century+periodicals+fairy+tales&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s, Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

Seitz, William C.. “Claude Monet”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Claude-Monet. Accessed 4 April 2024.

Schultz, Gretchen, and Lewis Carl Seifert. Fairy Tales for the Disillusioned: Enchanted Stories from the French Decadent Tradition. Princeton University Press, 2019.

License

The text of “The Heart’s Memory” is in the public domain.

All editorial material by Jocelyn Zheng is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- This could refer to the real kingdom of Ormus — or Ormuz in Portuguese after conquest by Portugal — which was located on the eastern side of the Persian Gulf. The name itself is derived from a pronunciation of the Persian creation deity, Ahuramazda, in Zoroastrianism. Ormus was established in the 11th century, occupied by Portugal in the 1500s, and annexed by the Safavid Empire in the 17th century. Today, it is part of the Hormozgan Province in Iran.↩︎

- In fairy tales, fairies are often known to bless newborn children with qualities such as beauty.↩︎

- a window sash that opens on hinges at the side↩︎

- relating to or taking place in the morning↩︎

- to or at a distance↩︎

- Christianity, specifically Catholicism, was the prominent religion in France during the time in which this story was written.↩︎

- (of a person’s face) having a healthy red color↩︎

- another term for sweetbrier (a small pink flower)↩︎