The Head

By L.E.L

Edited by Sydney Smith

From the Mind of LEL comes a story never before seen by today’s readers. Amalie, a young countess in late 18th century France, travels to the countryside with her wealthy husband. There she meets Julian, a Jacobite of the French revolution. The two begin an affair, and everything seems perfect, or is it….

Dealing with themes of Obsessive love and French History, The Head is a perfect read for enjoyers of history and twisted love stories.

Table of contents

- Editor’s Note:

- The Head

- French Revolution Timeline

- Artistic Response

- LEL: A Short Biography

- Works Cited

- License

Editor’s Note:

After a lot of searching through 19th century periodicals on google books, this story caught my eye. It might have been the title, something about “the Head” just sounds so ambiguous, or maybe it was the author, LEL, who I had never heard of before. Eventually I read the story in full and as a fan of both European history and Gothic writing, I immediately loved it. I later learned more about the author, LEL, who was plagued with scandal for the majority of her career, and looking back, knowing her back story makes this one much more interesting. Despite much critical acclaim, she is often forgotten as an author and some of her stories, like this one, have been lost to history. More on her life and work later in the biographical information on page 26.

My Original motivation for re-publishing this story was simply because I enjoyed reading it, and I thought others would too. However, as I began the editing process and started reflecting on how the Head can be reflected in today’s world, I saw that it is very applicable to our current society. Seeing how a relationship goes from loving, to obsessive, to abusive in a very short time period, made me think differently about relationships in the real world and how quickly they can turn sour.

The original text was written in English, but with small sections of French. I made the decision early on to keep this French, as I believe it further immerses the reader. Instead of translating it into the story I have added footnotes for translations. I, myself am not a French speaker, so I contacted my aunt, who teaches high school French and goes to France for a few months in the summer every year. All of the French translations in this edition are hers. I also added footnotes for historical context, if you are not a history fan like I am, I would still recommend reading them because they give extra context to the story.

The final decisions that I made involve the appearance of the story itself. As mentioned before, I am a big fan of Gothic prose (Edgar Allan Poe specifically), and even though The Head is a far cry from true horror stories, I still wanted to enhance the Gothicism of the story. The font I chose is very specific, it gives off a creepier vibe, with sharp letters that vary in thickness. I chose large margins to narrow the story down, which makes it look a lot more like the original periodical that it was published in (the keepsake 1834). Finally, I altered the textual coloring throughout the text, and although it is subtle, you might be able to notice that the text gets darker through each part as the story gets more intense.

Overall, I really enjoyed reading and editing this story. Its applications themes of obsessive love and abusive relationships are still very relevant in today’s world. Enjoy!

The Head

By L.E.L

The Countess Amalie de Boufflers was one of the very prettiest specimens of a pretty woman that Paris and nature have ever constructed. She had bright golden hair, always exquisitely dressed, whether sprinkled with powder, lighted with diamonds, and waving with feather, or suffered to hang in the studied negligence of a crop a l ’Anglaise. She had a hand as white as a lily and nearly as small; a foot and ankle as faultless as the satin slipper – which their artist said required the imagination of a poet to conceive, and the genius of a sculptor to execute; her walk was the most exquisite mixture of agility and helplessness that ever paid a cavalier the compliment of attracting his attention and requiring his aid; her dancing made the Prince de Ligne exclaim, “I understand the fables of mythology – Madame realizes the classic idea of the Graces.” Never did any body dress so exquisitely; Raphael himself never managed drapery to such a flow of elegance, Correggio never understood half so well the arrangement of colours, and in the management of fan, flacon, scarf, handkerchief, and bouquet she was unrivalled- “the power of science could no further go.” Beautiful she was not, for the imagination and the heart must enter into the composition of beauty – that beauty which is both poetry and passion; but, after all, there is no word in French that translates our “beautify,” and who in her own sphere could have desired her to be what their language did not even express? Numberless were the lovers whom she drown to despair – and many were those whom she did not! But all her petites affaires de Coeur 1were arranged in the most perfect taste; no scenes, no jealousies, no brouilleries; 2these are things which a femme d’esprit 3always avoids and, as the countess was wont to observe, “Je suis femme d’esprit par la grace de Dieu – et je le sais.4“

It was amazing in spite of all her avocations, how much she contrived to do for her husband: half at least of his pensions, places, and favors were owing to her solicitations; and this was very disinterested – for as they scarcely ever met, she had no motive for keeping him in good humour. Talk of the industry of the lower classes: — no woman with two cows, six children, to say nothing of pigs and poultry, and who takes in washing to boot, ever worked harder than the Countess de Boufflers; the poets whom she patronized; the plays which she protected, for a smile from the fair face bending anxiously from the box above, and meeting his gaze, quite by chance, disarmed many a stern young critic in the parterre5; — then the fashions with she invented; the financiers’ wives whom she put in the way of spending their husbands’ money creditably, i.e. as quickly and as uselessly as possible; her assiduous attendance at court and at mass; her thousand and one balls; her myriad of letters and notes, and above all, the inimitable suppers, of which she was the presiding deity; the piquant things which she said, the charming things which she looked, and the innumerable things which she did, proved, at least, that id idleness be the mother of mischief, she carefully avoided the parent, whatever she might do to the child.

Time past on as lightly as he always steps over flowers, Brussels carpets marble terraces, green turfs, or whatever simile may best express a path without impediment. Every day added one to the masses who adored her—people feels so safe in an admiration which is general. To think with others is the best plan of never committing yourself – the unsupported opinion runs such risks. But Fate is justly personified as a female, in so many caprices does she indulge; and one malicious fancy which she contrived was exceedingly displeasing to la belle comtesse6.

One night her husband entered her boudoir7; a surprise disagreeable on many accounts, but most disagreeable in its consequences. With that perfect ease which constitutes perfect good breeding, he announced that an affair of honour forced him to leave the court for a while, and while madame must be ready to accompany him to his chateau by daybreak. Amalie was horror-struck: she could have been so interestingly miserable about the count’s misfortune – so useful in arranging matters: such an opportunity for general sympathy might never occur again; but though she had not had many experiences of the kind, yet one or two instances of a divided opinion convinced her that when M. Le Comte 8did make up his mind, like the laws of the Medes and Persians9, it was not to be changes, and, it must be confessed, with no better reason. There is nothing in nature so impracticable as the obstinacy10 of your true husband; it is the insurmountable obstacle – the Alps no female vinegar can melt. Amalie knew her destiny, and submitted to it with as good a grace as she could. “Grace,” as she afterwards observed,” is a duty which a woman owes to herself on all occasions.” The count thanked her, kissed her hand, and bowed out of the room, leaving her to console herself as she could, and Amalie rarely wanted the means of consolation. We will only notice two principal sources; first, she had some rustic or rather romantic notions about innocent pleasures, interesting peasants, sheep, and roses growing in the open air ; secondly, it was a great relief to think of the sensation her absence would produce; she had quite comforted herself while she reflected on les miserables 11whom she would leave behind; she also felt a little touch of curiosity when the count desired her company; she became almost interested about him while thinking what could be the cause. It was but a little mystery, scarcely worth penetrating, if she had known all. De Boufflers was himself in despair at leaving Paris and was only induced to take so rash a step from considering that his own chateau was preferable to the Bastile12. In an agony of anticipated ennui, he looked about for a resource; his wife’s evil genius managed that her idea should occur to his mind. Everybody dais she was so charming, would not her company be better than none at all—or, worse than none at all – his own? The Comte doe Boufflers was himself “the ocean to the river of his thought,” and he decided that it was far better for half the Salons in Paris to be désolés13 than to omit even so slight a precaution as his wife’s company, when reduced to sixty miles for Paris, tapestried chambers, Some fifty worm-eaten portraits, and an avenue with a rookery.

The next morning Amalie, who had made up her mind to enact la femme Comme il y en a peu14[,] was ready and that both drove off rapidly after a conjugal dispute as to whether both her pet poodle and paroquet were to have a place in the carriage, but, as it is usually the case in trifles, female supremacy carried the day. For many miles the countess was kept awake by hope and reflection; the hope, a sort of vague, romance-reading hope, that some adventure would fall out by the way, and the reflection on the despair which her sudden departure would occasion. At length her imagination and her temper were alike exhausted; she became sleepy and petulant and if such a term could be applied to any form of speech proceeding from a mouth whence spring had copied its roses (we merely translate into prose an expression in the last copy of verses addressed to the divine Amalie), she actually scolded, her poodle barked and snapped, her paroquet screamed and bit, and when they arrived at the end of their journey, the count was plunged into a profound meditation as to what other people could find so fascinating in his wife.

The chateau was, like the general run of chateaux left to a concierge and one or two old retainers, as dilapidated as their dwelling. A ghost had taken possession of one chamber—smoke of a second – a murder, ages ago, had been in a third—and a fourth swarmed with rats. The count sought refuge in shooting partridges from morning till night, and the countess in despair and letter-writing. There is such a as friendship, for her epistles received answers full of condolences, regret, and, dearer still, news. One letter, however, from l’amie intime15, Madame de Betune, made her feel almost as desperate as people do when they tear their hair, frown themselves, pay their debts, or commit any very outrageous acts of extravagancy. The precious yet cruel scroll gave a full and particular account of a late feté16 at Marli17. Marie Antoinette18 had decided on a taste for rural and innocent pleasure, and the whole court had grown rural and innocent to a degree. Nothing was to be seen but crooks, garlands, straw hats, and “white frocks with broad sashes,” quite English: then they had a real-earnest mill and a boat, and the gardens were filled with groups enacting rustic scenes. It was enough to provoke a saint – though Amalie made no pretensions to such a character, whatever she might to that of an angel, to have everybody else playing at a country life, while she was acting in reality. But the worst was yet to come; the part selected by the queen herself for “sa belle Amalie”19 had of necessity been given to Madame de Mirvane,”who,” pursued her informant, “looked pretty enough, but managed the dove, which she was to sit beneath a tree caressing, with no sort of grace. How differently would It have been perched on your mignon20 fingers! It was dreadful that such an interesting part, so simple and so tender, should have been so utterly wasted; but this will make her majesty still more in earnest about obtaining M. de Boufflers’ return. What business has notre bon homme21 Louis with a gentleman’s affair of honour?” The only consolation which the countess could devise was to try how the new and simple costume would suit her; she could at least have the satisfaction of her own approval. The next day say her seated beneath an old tree in the neglected garden through whose boughs the sudden sunshine fell half green, half golden, as the light of the noon and the hue of the leaf mingled together. Her hair was carelessly combed back under a wide black chip hat, with just un noeud du ruban22 ; she wore the simplest of white dresses; and, as no dove could be procured, her paroquet was fastened with a silken string, and placed in an attitude on the prettiest hand in the world. But alas! Projects fail, strings break, and birds fly away, even from such a jailer as la belle23 Amalie.

suddenly the slender fastening gave way, the paroquet spread its wings and was soon, and was soon lost amid the branches. In such a case there is by one resource, and the countess executed a most musical shriek; this being of no avail, ” tears were in the next degree;” but the countess had no idea of wasting such interesting things as tears on herself, so she was returning to the chateau for assistance to recover her fugitive, when a rustling amid the boughs overhead attracted her attention, wand the next moment a singularly handsome young man sprang to the ground and presented her bird.

“Ah perfide24!” exclaimed Amalie, overwhelming her favourite with caresses—upon principle—for affection is the sign of a good heart, and simplicity was not only so engaging, but in such exact keeping with her costume!”But I am quite ungrateful with delight,” turning to the young stranger, who was gazing upon her with evident admiration; and raising, but for a moment only, her eyes to his face, “I really know not how to thank you enough.”

“Ah, madame,” exclaimed the youth, “I am but too fortunate,” and he stopped, embarrassed, but reluctant to depart: — the countess had no intention that he should.

“How could you,” continued she, glancing with a slight shudder at the old chestnut tree, from which he had just descended, “trust your life amid these decaying branches?”

“Ah, even my attachment to ce pauvre cheri25 is a selfish pleasure;” and, lost in the terror her fancy had conjured up, and the philosophic reflexion it had inspired, Amalie seated herself on a projecting root, whose moss was beautiful enough to have been an artificial covering. The stranger stood at a little distance, and even Amalie felt something very like confusion at his earnest and prolonged gaze; for homage she was always prepared, but sincerity took her a little buy surprise—however, the novelty made the affair more piquante26.

“Monsieur does not belong to these parts?” Now there was insinuated flattery in this negative method of putting the questions; it was as much to say, it was impossible they could have produced him.

“I am a native of the adjacent valley.”

“Strangers alike up out native soil, I suppose?” said Amalie.

“I have passed the greater porting of my life here.”

“Indeed!” exclaimed she; “but I can see that you have travelled.”

“I spent two years in England.”

“As everything English is the rage just now, I dare say you recognize my dress.”

The young stranger was forced to confess that he did not, and he avowed that he had attended but little to the affairs of the toilette during his absence; but his manner implied that he had now seen one that he should not readily forget. Well to cut the conversation much shorter than the countess did, they parted, with a light hint just dropped by Amalie, that she now passed the greater portion of her time in solitude, and that the old chestnut was her favourite haunt. The next day she was there, and the young stranger passed quite “accidently”; however, she had to show him how much more securely the paroquet was fastened to-day; one word led to another, and the conversation was long and interesting. Amalie discovered that the youth’s name was Julian; and that he was a democrate et misanthrope27, but she undertook to convert him. Even with the very prettiest of preceptor’s conversion is not the work of a day; so, leaving it to its progress, we will take the opportunity of stating who Julian was – alas! A roturier28.

His Father had carried on an extensive trade in precious stones, had traveled much, and profited in more ways that one by his travels; he early realized a competence, and what is much rarer, early began to enjoy it. He married an English girl, and settling in the valley where he was born, led a life of seclusion, study, and domestic content – a state of existence so often a dream and so rarely a reality. Julian was brought up with every care; his natural talents were cultivated as sedulously as books could cultivate them. But the knowledge of the library is not that of the world; a youth of solitude is bad preparation for a manhood of action; from the earliest age we need to mingle with our own kind the child corrects and instructs the child more than their masters; our equals are the tools wherewith experience works out its lessons; and the play-ground, with its rival interests, its injustices, its necessity for the ready wit and the curbed temper is both miniature and prophesy of the world which will but bring back the old struggles only with a sterner aspect, and the same successes, but with more than half their enjoyment departed.

The death of Julian’s mother was soon followed by that of his father, and at nineteen the youth was left to a world from which he turned with all the desolation that attends on the first acquittance with sorrow and death. The affection between himself and his parents had been so strong and undivided, that life seemed left without a charm when bereaved of their love. Youth suffers but for a season; the bowed but unbroken spirit resumes its elasticity; the future, unknown and beautiful, wins the present to itself, and the past waits for that dark and overwhelming influence with sooner or later will darken our whole horizon.

Julian arrived in Paris – his heart full of passion, and his head full of poetry—the one to be deceived, and the other to be disappointed. His wealth, his prepossessing appearance, and some scientific introductions, for his father had been the correspondent of eminent men, opened to him several of the first houses in Paris; but society soon made him aware that we was only there on sufferance;29 that “thus far and no further,” was the motto of aristocratic courtesy; he felt himself the equal – ay, the superior—of half of the gracious coxcombs30 that surrounded him, and yet an accident of birth and fortune placed him at an immeasurable distance from those whose manner mocked him with the semblance of equality. It was one of the greatest vices of the old French regime, that there was no opening for the energy, the enthusiasm, or the genius, of the middle rand; that rank which in England is constantly renovating the upper classes and which may, at least, aspire to any distinction. But in France, ” the sword, gown, glory” did not ,“offer in exchange” for industry and talent; and a highly educated young man of independent fortune, but of plebian extraction; — from his wealth lacking the only pursuit allotted to his class – was like an animal in a menagerie, the most misplaced object in creation, debarred from all healthy and natural exercise, yet able to see the free boughs and far prospect while confined to a great perch and a narrow cage. But the tyranny of custom, like all other tyrannies, when grown quite unbearable, for it is wonderful what people will endure – had already sown the seeds of its own dissolution. Out of the hardship had grown the reining, and to repine at the exercise of an alleged right is soon to question its authority, and the first question asked shakes the whole ancient and time-honored fabric of privilege. A fierce and restless spirit of change was at work – and only that the future, despite of history, was never yet foretold from the past, a sudden and terrible re-action might have been foreseen. But we have nothing more to do with revolutionary principles that to mark their effect on the mind of Julian, which soon became imbued with the wildest of the doctrines then afloat; to the young it seems so easy to mend everything, simply because they have not tried. Perfect equality, and a prefect despotism, are theories equally unreducible to practice; but there are many fine sentiments belonging to the first, and there us a singular fascination in a fine sentiment – we pay ourselves a compliment by uttering it. Julian heard the errors of “the present state of things” so often dilated upon that he doubted whether there was anything really right on the earth; however, he was fortunate in the belief (a common patriotic delusion, by-the-by,) that himself, together with a few chosen others, were destined to set everything as it ought to be, and the sooner that such a destiny was fulfilled the better. In the meantime, an affront at a gaming-table from the Chevalier de l’Escars31, for which satisfaction was afterwards refused on the plea he could not fight a roturier, drove Julian’s naturally violent temper almost to insanity. Degraded in his own eyes, he fancied everyone must feel as he did, and abjured a world to which he imagined he was an object of scorn, while in truth he was the only one of indifference. There is one conviction at which, though forced upon us by daily experience, we never arrive namely, the conviction that Nobody in reality cares for Anybody; but this truth is do cold that we fence it out by all sorts of cloaks and coverings, delusions and devices. Well, Julian retired to his native valley, to brood over schemes of public benefit and private revenge; but at two and twenty it is as much trop tot32 for a man to be a philosphe33 as it is for a woman to be a devote34. Les beaus yeux35 of Madame de Boufflers put to a flight a thousand schemes for the regeneration of mankind, and Julian forgot wrongs, projects, equality, unity, and the rights of the human race, at the feet of the pretty aristocrat.

PART II

A low, will wind moaned through the streets of Paris, and a dull, small rain scarcely penetrated the thick fog which hung on the oppressed atmosphere: — in a high wind and a brisk shower there is a something that exhilarates the spirits; but this damp, dreary weather relaxes every nerve, unless indeed they be highly strung with some strong excitement, that defies every external influence – but, ah! Of such life has but few instances. All great cities present strange contrasts; the infinite varieties of human existence gathered together mock each other with the wildest contrasts; and if this is true of all cities and all times, what must it have been in an hour like that of which we now write, and in a capital like Paris! The revolution was now raging in all its horrors; a terrible desire for blood had risen in the minds of men, and cruelty had become as much a passion as love. In one street a band of ruffians insulted the quiet night with their frightful orgies: in the next a worn and devoted family clung to each other, and trembled lest the wind as it moaned past might bring the footsteps of the ministers of a nation’s vengeance, or rather of a nation madness. Here was a prison crowded with ghastly elements of human wretchedness and crime, were in commotion, and Paris was filled with riot and change. Yet into one luxurious haunt of rank, wealth, and grace it would seem as if no alteration had made its way. The blue satin draperies of the little boudoir, which was fitted up as a tent, were undisturbed, and the silver muslin curtain reflected back the soft light of the lamps; while roses on which months of care had been bestowed for an hour of lavish bloom, the red light from the cheerful hearth, the rich carper, over which the step passed noiseless, the perfumes that exhaled their fragrant essence—all mocked the desolation without. Leaning upon a couch near the window was the Comtesse Amalie, pretty as ever changed in nothing save costume, which as suited to the classical mania of the day; her hair was gathered up in a Grecian knot, the little foot wore a sandal, and the white robe, a l’ántique36, was fastened by cameos37. Suddenly a door opened—and the rain damp upon his cloak, and his hair glittering with its moisture entered Julian; he was changed, for he looked pale and exhausted, and lip and brow wore the fixed character and the deeper line which passion ever leaves behind. Amalie rose, and, with an expression of the tenderest welcome, took his cloak from him, and with her own mignon hands drew the fauteuil38 towards the fire, and placing herself on a little stool at his feet, looked up in his face with an asking and anxious gaze, perhaps the most touching that a woman’s features can assume to her lover. Amalie did not love Julian as he loved her – it was not in her nature—but her light and vain temper was subdued by his earnest and impetuous one; she feared him too, and fear is the great strengthener of a woman’s love. Besides there is something in intense passion that communicates itself, as the warmth of the sun colors the cloud, whose frail substance is yet incapable of retaining the light or heat. Amalie had no sympathy with the poetry of his character; but it gave grace to his flattery and variety to himself, to say nothing of the advantage of contract with all her other adorateurs39. Moreover, his influence with the Jacobin40 clubs had warded off dangers that had crushed other families noble as that of the De Boufflers. Julian, like all of an imaginative turn, deceived himself and worshipped an idol which he had created rather than an object which existed: a pretty face blinds even a philosopher, and from habits of seclusion and naturally refined taste, he was peculiarly susceptible to the charm and ease of her manners. Perhaps—for the wheat and tares of human motives spring up inextricably blended—the young democrat was somewhat dazzled by the rank of the charming countess. I always suspect that the professed despisers of all worldly distinctions take refuge in disdain from desire. For some time Julian sat in moody silence, his gaze fixed on the wood embers, as if absorbed in contemplating their fantastic combinations. Amalie changed her attitude, rallied her lover on his abstraction and asked him if it was fair to seek one lady’s presence and then think of another.

“Think of another!” exclaimed he, springing from his seat: “Good God, Amalie! Is there one moment fevered and hurried as is my existence, in which you are forgotten? I love you terribly! Ay, terribly! For it is terrible to have one’s very soul so bound up in but one object. I would rather at this very moment see you dead at my feet than ever dream of you as loving another.”

The countess turned pale.

There was nothing in herself that responded to this burst of passion and terror was her paramount sensation. “You are too violent,” said she, in a faltering voice.

“Too sincere, you mean,”replied he. “Amalie, our present life is intolerable; — I cannot endure longer these stolen and brief interviews. Why should we thus waste life’s short season of existence? We shall not live long, — let us live together. Amalie, you must fly with me.”

Madame de Boufflers looked—what she was – astounded at this proposition. “What nonsense you are talking to-night,”answered she, forcing a laugh.

“You do not love me!” and his clear light eyes flashed upon her with a strange mixture of ferocity and tenderness.

She shrank before the glance, and whispered, “If I did not love you, why are you here? But think of the scandal of an elopement; les convenances41 of society must be respected.”

“Curse on these social laws! Which are made for the convenience of the few and the degradation of the many. Amalie, I cannot, will not steal into the house of that insolent aristocrat, your husband, like a midnight thief. You must leave him, and let my home become yours. I will watch over you, — pass my life at your side, — anticipate your slightest wish, — but you must be mine own. The law for divorce will soon pass the Assembly, and then let me add what tie or form you will to the deep devotion of my heart, my own my beloved Amalie as my wife.”

“Your wife!” Interrupted by the countess, old prejudices springing up far stronger than present feelings. “How very absurd; think for a moment of the difference in our rank.”

A spasm of convulsive emotion passed over his face, the veins rose on the high forehead, the blood started from the bitten lip, but in an instant the expression was subdued into a stern coldness; and if Julian’s voice was somewhat hoarse the words were slow and distinct. “Amalie,” said he, taking her hands in his, “my whole destiny turns on the result of this interview. Have you no fear of my despair?”

Amalie could have answered that she felt very sufficiently afraid at that moment, but for once in her life she was at a loss for a reply; she remained silent, almost embarrassed, certainly bored, –and Julian went on.

“I will not shock your gentle ear by words of hate against the class to which you belong; but a fearful reckoning is at hand; and am among those who will exact it to the uttermost. I warn you fly from them – be mine, for your own sake.”

“Really, Monsieur42 Julian,” said she, “your conduct tonight is most unaccountable. Come, do pray be a little more amusing.”

“Monsieur Julian!” repeated he, in a deep whisper; “is it come to this? Amalie, do, I implore you, think how desperately I love you. You may believe that on your part has been the sacrifice; but what has it been on mine? For your sake I have trifled with rights I hold most sacred; I have tampered with mine own integrity; I have held back from the great task before me; I have been a faint and slow follower of that glorious freedom which now calls aloud on all her worshippers for the most entire devotion; and yet I have shrank back from the appointed duty. Amalie, come with me – be my inspiration; feel as I fell, think as I think, cast aside the idle prejudices of a selfish and profligate court, and be repaid by passion as fervent, as fond, and as faithful as ever beat in a man’s heart for a woman of his first-and-only love.”

“This is really too much of a good thing,” thought the countess, whose mind wandered from the love before her to the scandal and ridicule likely to be caused by her flight.

“Il Faut respecter les convenances43,“ was her chilling reply

Julian dropped her hands and approached the door; he opened it, but he lingered on the threshold. “Do you let me go, Amalie?” whispered he in a scarcely audibly voice.

“I am sure.”

“You have not been so agreeable that I should wish to detain you.”

The door closed. His rapid steps were heard descending the narrow staircase; at length they died away.

“I really must put an end to this affair, it is becoming troublesome; my young republican is growing pedante et despotel44. He has none of the graces of my cousin Eugene.” And Madame de Boufflers threw herself into the fauteuil, and indulged in a discontented reverie, in which Julians faults and Eugene’s merits occupied conspicuous places; together with the garniture of a new species of sandal which she meditated producing. In the meantime, Julian pursued his way through the dark and dreary streets, suffering that agony of disappointed affection which the heart can know but once. Love is very blind indeed, but let the veil once be removed, though for a moment, and it can never be replaced again. Then how quick sighted do we become to the errors of our past worship, and mortification adds bitterness to regret. “And is it for one,” exclaimed he, “who holds the factitious advantage of a name, to be better worth than my deep love, that I have sacrificed the cause to which I was vowed, and have paused on the noblest path to which man ever devoted his energies? But the weakness is over; a terrible bond shall be made with Liberty—Liberty henceforth my only hope, my only mistress!”

The evil spirit of love left his soul for a moment, but returned, though with a strange and lurid aspect, bringing with him other and worse spirits than himself—hate, revenge, blood-thirstiness—all merged in and colored by the excited and fanatic temper of the time. He stopped before a large hotel, from whose windows the red light glared, as it mocked the darkness of night as much as the revel within did its silence. There was that mixture of luxury and disorder which once so shocks and attracts the imagination. Its hangings were silk, the chairs and sofas satin, but they were torn and soiled; the servants were many, but ill-dressed and awkward; all the light elegance for which the hotel had been noted in its former proprietor’s life (the Due de N. had perished by the guillotine45) had disappeared; the character of its present master was impressed on all around him. A door opened into a vast chamber crowded with fierce and eager faces, every eye assuming the expression of murder as the rightless Danton called down their vengeance on those whom he denominated their old and arrogant oppressor.

“Some there are,” exclaimed he, as he caught sight of Julian’s pale and expressive countenance, “who delude themselves with the belief that their own preferences are sufficient cause for exception – who merge the public cause in private interests. What are such cowards a traitor? Unworthy to bring one stone towards the great temple of liberty about to overshadow the world, but whose foundations must be laid in blood – ay blood!”

A hoarse and sullen murmur rather than acclamation ran through the crowd, and a few minutes elapsed ere the business of the night proceeded. Then began those fearful denunciations, which seemed to loosen every tie of nature—the father witnessed against the son, and the son against the father; the young, the aged, the innocent, the beautiful, were alike marked as victims. Suddenly Julian arose: a close observer might have noted that his brow was knit, as it is in inward pain, that his lip was white, as if the life-current had been driven back upon the heart, prophetic of the future, which doomed it to freeze there forever; but to be careless wye he seemed stern, calm, ferocious as the rest, while he denounced Amalie, Comtesse de Boufflers, as an aristocrat, and an enemy to the people. Danton looked at him for an instant, but cowered before the wild fiery glance that met his own.

To denounce, to condemn, to execute, were, in those ruthless days, but the work of four-and-twenty hours. The next noon but one an almost insensible female form was carried or rather dragged to the scaffold. It was the Comtesse Amalie.

Her long bright hair fell in disorder over her shoulders.

The executioner gathered it up in a rough know

he had been told not to sever it from the graceful head.

At that moment the prisoner gave a bewildered stare around.

A wild gleam of hope illuminated her feature.

she stretched out her arms to someone passionately in the crowd.

“Julian save me!”

The executioner forced her onto the table;

The blade glittered in the sun.

And the head fell into the appointed basket.

A convulsive motion shook the white garments around the quivering trunk.

PART III

“I looked on the faces of his judges, and felt there was no hope,” said an old man as he led away the promised bride of his son, now a prisoner, doomed to death on the morrow.

“yet the one they call Julian looks so young, so pale, and so sad, there is surely and implore him for mercy of Frederic.”

The old man shook his head, but accompanied her to Julian’s hotel, where the eloquence of some golden coins procured her admittance. She found her way to a large and gloomy chamber, where he sat surrounded with books, papers, and charts, mocking himself with a frenzied belief in the coming amelioration of the world, while his own home was a desert, and his own heart a desolation. He did not perceive the fair and agitated creature that knelt at his feet, till her supplicating and broken voice roused his attention. He listened till her words died away into the short thick sobs of utter agony, unable to bear the picture it had conjured up of its coming wretchedness.

“Pity from me!” he exclaimed, with a quick fierce laugh; “Pity! – I do not know the meaning of the word. You might as well address your prayers to yonder bust of the stern old Roman, who sealed his country’s freedom with the life-blood of his child.”

The girl unconsciously looked towards the harsh features, made yet harsher by the black marble in which they were carved. And she started, for she felt that even that stern and sculptured countenance had more of human sympathy than the pale lip and cold eye of the living listener; yet love is desperate in its hope; she flung herself at his feet, she hid her face on the hand which she grasped, for she dared no look up and meet that fixed and passionless face; but still she pleaded as those plead who pray for a life far dearer than their own.

“He is so young –so good –there is so much happiness before us; his poor old father will die—he has no other child—and I—he must not look to me to supply his place. God of heaven! Have you never loved—have you no recollections of affection that can move you to pity others!”

“I have!” said Julian; and rising from his seat he took the arm of the agitated girl, and led her to a recess in the apartment, and drew back a curtain.

Horror for a moment suspended every other feeling; for, laid upon a cushion, the long fair head streaming around, was a female head preserved by some curious chemical process; the eyes were closed, but as if in sleep; colour had departed from lip and cheek, but as it in sleep; colour had departed from lip and cheek, and something beyond even the rigidity of stone was in the face. The petitioner turned from the dead to the living, whose ashy colour, and wild fierce eye, struck more terror to her soul than the mournful mockery of the head, where life’s likeness was fearfully rendered. Julian gazed on the dread memorial which he had snatched from the scaffold, with that strange mixture of hate and love, the mind’s most terrible element, whereof comes despair and madness; then turning slowly to the bewildered girl, said, in a low voice, but whose whisper was like thunder when the flash is commissioned to destroy, —

“That head belonged to my mistress—she was an aristocrat—and I denounced her—Judge if there exist one human being whom my pity is likely to spare.”

His wretched petitioner gazed upwards, but hopelessly, and staggered against the wall.

“I would be alone,” said Julian, and led her to the door, she left him silently. She now knew prayers were vain. That night her lover perished beneath the guillotine; — the same blow struck to the heat of the fond and faithful girl – death was merciful, for both died at the same moment. By some inscrutable sympathy with the love which yet moved him not to spare, Julian had them buried in the same grave.

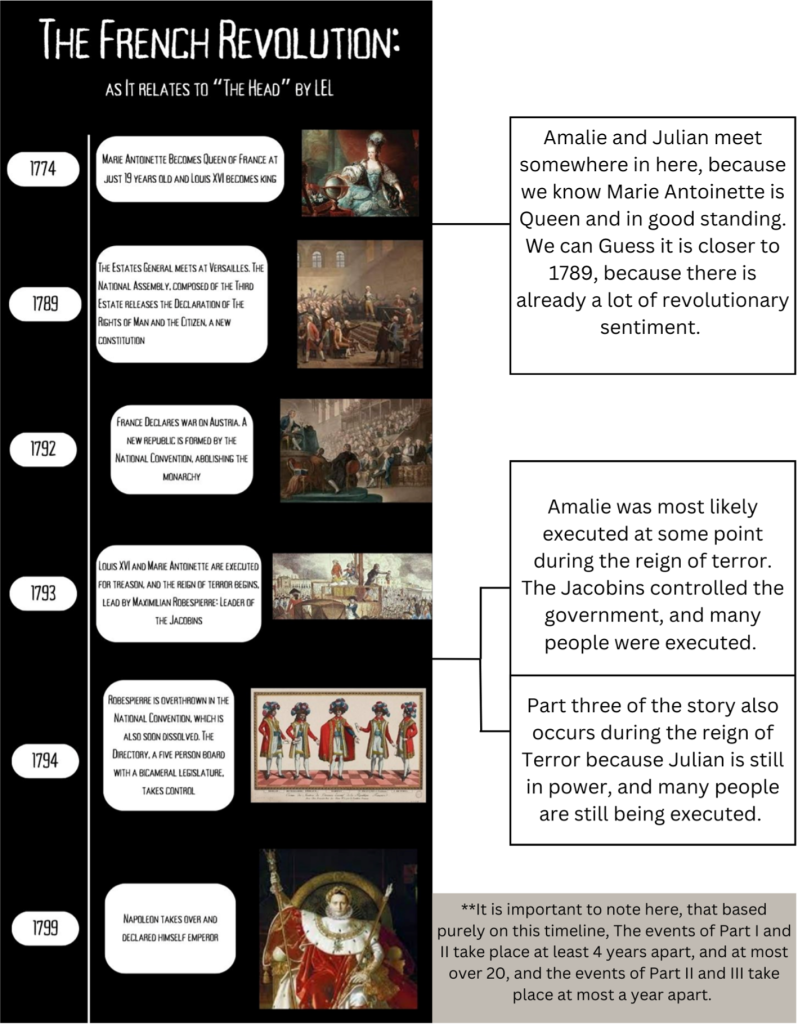

French Revolution Timeline

The Guillotine, an Artistic Response

What’s the difference between a convict facing the guillotine and a baseball player? One goes “Thwack, Darn” the other goes “Darn, Thwack”.

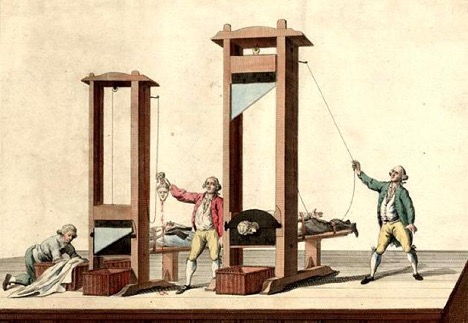

At the height of the French Revolution, known as the reign of terror, no symbol was more significant than the French Guillotine. In The Head, the main character, Amalie, is executed during the reign of terror, likely by a guillotine. In addition, the guillotine is an important representation of the story. As part of this republication, I have redesigned and modeled the guillotine based off of original images of executions taking place during the French revolution. The history of the guillotine as a device of terror, helps us better understand the context of the French Revolution, and its symbolism of the story itself helps better understand The Head.

The invention of the guillotine was a true representation of revolutionary ideals. While it is often associated with death and terror, the guillotine was actually originally thought up as a way to make executions more humane (Brittanica). Joseph Guillotin originally proposed the idea to the estates general in 1789. He wanted to design a machine that was both fast and painless. Before the invention of the Guillotine, “public executions had derived much of their ritual drama from the prolonged suffering of victims,”. Beheadings did occur but were often only reserved for the convicts belonging to high-society. In 1789, the only legal form of execution became beheading by the guillotine. This meant everyone, no matter their social status or wealth, faced death in the same quick, painless way (Carrabine).

During the Reign of Terror, Public beheadings were very common. It is estimated that “as many as 17,000 people were guillotined, including King Louis XVI,” (Grey). Public executions on their own were quite popular to go and watch, but the addition of such a terrible machine as the guillotine drew in more people than ever. The guillotine was so popular in fact, that even after the French revolution, travel agencies would take tourists to see them over some of the other big attractions in Paris. Suffice to say, the guillotine quickly became “the most notorious,” symbol of the French revolution (Carrabine).

In terms of The Head by LEL, the guillotine acts as both a symbol and as a way to better immerse the reader into the time period. The word guillotine is actually only mentioned once throughout the story on page 14 when the Text states, “the light elegance for which the hotel had been noted in its former proprietor’s life (the Due de N. had perished by the guillotine) had disappeared” (Landon). This may seem insignificant, but it truly puts the reader in the mindset of the reign of terror because the execution is mentioned so casually. It tells the reader this kind of thing happens all the time. In Addition, it is very likely that Amalie perished under the blade of the guillotine because of her social standing and the time period.

While working on this project, I realized that the guillotine is also very representative of the story as a whole. The swiftness with which the guillotine killed its victims is representative of how fast the plot goes from lighthearted to dark. This plot structure is also found in other stories. Some might even consider it to be a plot twist, meaning the story goes in one direction and then takes a sharp, shocking turn in another direction. Stories like Sarrasine by Honore de Balzac, which start relatively slow and end with a surprising turn of events also have this twisting plot. Additionally, the love that Julian and Amalie share appears to be pure (or at least as pure as an affair can be), but quickly becomes obsessive. The guillotine itself is similar, it was made to be more gentle form of execution but became a symbol of cruelty. This theme of false expectations is present in other stories too, such as Tobermory. In Tobermory, a scientist trains a cat to talk, but everyone quickly realizes that Tobermory (the cat) knows all their secrets, which he can now share thanks to his new ability. Tobermory the cat is a perfect literary example of leading the reader into a false sense of security. The Head does something very similar in terms of Amalie’s and Julian’s relationship, which is symbolized by the Guillotine.

As mentioned earlier, I have redesigned and created a virtual model of the guillotine. I based most of my design off of pictures from executions in the 18th century such as the one below. Outside of that, not much is known about its structure. The relative scale of it was 14ft tall, and we know that it was “heavily weighted to make it fall forcefully upon (and slice through) the neck of a prone victim,” (Britannica). I made a track in the main frame, to keep the blade straight as it makes its descent. There is no rope in my CAD design, mainly because I was unable to properly represent it. The rope would have been tied to the blade via the loop attached to it, it then would have looped through the top eyebolt on the main frame. From there it goes through a hole on the side of the main frame, then is tied to the eyebolt on the side of the mainframe. As far as materials go, based on pictures, the majority of the body was made of wood. The only metal in the structure appeared in places that experienced high mechanical stress and the blade. I have colored things that I think might have been built out of wood in blue, and things that would have probably been made out of metal with green.

The guillotine played a major role in the French revolution and the story, The Head by LEL. In this Digital edition I have redesigned and created a digital rendering of the original guillotine from the French revolution based on pictures drawn at the time. While many associate the guillotine with death and cruelty it actually acted as a way to level the playing field between nobles and commoners, who were convicted and executed. In theory, it was a perfect representation of revolutionary ideals, but many people were convicted and killed without a trial within a matter of days just like Amalie in The Head.

LEL: A Short Biography

For one of the most famous authors of her time, LEL has somehow been forgotten. Often described as the Female Byron, Letitia Elizabeth Landon inspired Edgar Allan Poe along with other later writers. By the time she was 25 she had published several acclaimed novels, countless poems, and several short stories. So, the question remains, why is she so often left off the list of great English writers of 1800s. LEL lived in a world where women had no sexual freedom or really much freedom at all, and once word got out that she had been sleeping with her mentor, William Jerdan, she quickly became a social pariah. The gossip and scandal prevented her rise to the top of society, caused a broken engagement, and might even have contributed to the lingering questions around her death. It is also well known that many of LELs works were inspired by her own life and “The Head” is no exception. It is almost certainly related to Landon’s relationship with her long-time mentor and Lover, William Jerdan.

Letitia grew up comfortably, her father was relatively wealthy, and her mother was well connected. Trained in poetry from an early age, she was largely considered a child prodigy in her young years (Foundation). However, her troubles started in the late 1810s when her father faced bankruptcy and eventually abandoned the family. He later died around 1823 in some sort of backwater. In order to make ends meet, the family sold their nice house, and downsized (Miller, 58). Before they moved, Letitia caught the eye of a middle-aged man next door, William Jerdan, who was chief editor of the Literary Gazette, a prominent periodical in England. Letitia’s governess and her mother introduced her to Jerdan and eventually she became a consistent contributor to the Gazette. Jerdan became both a mentor figure and lover to Letitia (Miller, 66). As a young woman she was completely taken by him, and wrote many poems of “passionate love,” (Brittanica), despite the fact that Jerdan was already married and often took credit for her work.

The relationship Between Letitia and Jerdan continued almost up until her death. In the beginning, the young poetess was completely enthralled with him. Throughout the course of her lifetime, she ended up bearing Jerdan 3 children, all of whom she was forced to give up preserving her reputation in the eyes of polite society (Miller). As LEL got older, she climbed the ranks of the Literary Gazette, eventually becoming one of the co-editors. Despite all of this, she grew increasingly unhappy. Jerdan eventually started sleeping around with other women, fathering several more children. He seemed to be done with Landon, despite all of her contributions to his business and all the sacrifices she had made for him. At the time the Head was published in 1834, Jerdan had all but completely abandoned the once glimmering diamond of the London literary scene, as she became “a burden to him,” (Miller 213). The parallels between the Head and the story of Letitia’s relationship with Jerdan are almost uncanny.

In the Head, a young Jacobin, falls for Amalie, a countess, who is high in the ranks of Society. After several years of the affair, Julian proclaims his love for Amalie and tries to convince her that they should run away together. Amalie rejects him because of his social standing, for he is just a commoner. Julian ultimately becomes very upset and orders Amalie’s execution, keeping her head. While Jerdan and Letitia’s relationship most certainly did not involve murder, they did have a similar relationship. Landon seemed to be much more taken by Jerdan than he was by her. She was just another talented young writer to him ̶̶ He courted several in his lifetime ̶ . Like Julian, Landon was ultimately rejected by Jerdan even after she sacrificed so much for him. She risked her reputation, career, and children on him, and he still threw her away like old garbage. The way she felt was probably very similar to the way that Julian felt after being rejected by Amalie: angry. While Letitia definitely did not Kill Jerdan, maybe she wrote this story as an outlet for her anger. With Letitia acting as Julian, the similarities do not end there.

One of the other big influences on “The head” was Landon’s trip to France in 1834. their relationship seemed to continue even though Jerdan became less interested in Letitia as she got older. In early 1834, Letitia accompanied one of her few friends to France, where they stayed for several months, so that she could “get scenes for her next novel,” which would take place in the latter part of the revolution (Matoff). While in France, Letitia and Jerdan still wrote to each other. At first, their usual playful tone continued, but Jerdan began replying more intermittently. At one point Letitia even “berated him for not responding,” (Matoff). It is already known that she was considering writing another story in which the main character was killed via guillotine, probably the same one that she wanted to research in Paris (Miller 169). That project was scrapped, but perhaps the head was written instead, especially considering the timeline of her relationship.

Despite all of her critical success and fame, Letitia was plagued by Gossip for the majority of her career. She often struggled with her social status, leading to depression and issues with her personal relationships. Early on in her career, Letitia often “flaunted her affair with Jerdan,” (Miller), still young and naïve. The relationship eventually became fairly well known in London literary circles, but as LEL’s fame increased as an author, speculation began to occur surrounding her personal life. In January 1826, News of the affair hit the streets when the Times published an article with the headline “Sapphics and Erotics” (Victorian Web). Letitia’s popularity quickly plummeted. Several magazines, such as the Sunday Times and the Wasp, dragged her name through the mud. Letitia’s lack of a social circle outside of Jerdan left her isolated and feeling very depressed, so much so that “suicide was often a common theme in many of her works,” (Miller). The effect of her falling social status was also often seen in many of her works. Many of her later pieces were much more righteous and wholesome, a far cry from the passionate poems of her early career. The relentless gossip not only influenced her career, but her personal life as well. After the end of her relationship with Jerdan, Letitia moved on with another man, John Forster. Forster was much younger than Letitia and a fellow member of London’s literary scene. They eventually got engaged and were close to marrying when Forster found out about Letitia’s sexual history. The relationship quickly ended, leaving Letitia alone again. Considering Letitia’s experience with Gossip, there are even more lines that can be drawn between her and Julian.

In the Head, there is a lot of detail given on Julian background and his life as a young man. Once he became independent, Julian went to Paris for a while. However, while he there he was looked down upon by all the members of Parisian society due to his social status even though he believed himself much smarter than everyone else in the room. It was because of this that he became a Jacobin, and probably why he had repressed anger so much for Amalie, who was a member of the social class that had taunted him so many years before. Letitia had a very similar experience with London’s fine society. At the height of her career Letitia attended many parties and seemed to have an abundance of friends. As soon as word of her affair hit the streets, she found herself friendless and alone. This must have created some form of disillusionment with society, as reflected in the characterization of Julian in The Head.

LEL’s death was just as tragic as the rest of her life. After finally marrying, Letitia moved to cape coast with her new husband, George Maclean. Less than a year after the marriage, on October 15th, 1838, that her body was found as a result of a supposed overdose on prussic acid. It is presumed that she either committed suicide or accidentally overdosed, but how she got her hands on such a large amount of the substance is unknown. Willaim Jerdan eventually went bankrupt and became very involved with Maryann Maxwell, fathering at least one more child by her. Much of what we know about LEL and Jerdan’s relationship is from his autobiography in 1852, where much of their correspondence can be found.

LEL lived a tragic life, which while very unfortunate, inspired hundreds of critically acclaimed poems and stories, such as the head. This particular story was inspired by the gossip she endured, her trip France, and her 12-year relationship with William Jerdan. She is widely forgotten because of her poor reputation, but she was one of the greatest writers of her time and should be remembered as such.

Works Cited

Carrabine, E. (2023). The guillotine: Shadow, spectacle and the terror. Crime, Media, Culture. https://doi.org/10.1177/17416590231218744

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, February 20). Guillotine | Facts, inventor, & History. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/guillotine

Encyclopedia Brittanica. “Letitia Elizabeth Landon | British Author | Britannica.” Www.britannica.com, 20 Mar. 2024, www.britannica.com/biography/Letitia-Elizabeth-Landon.

Foundation, Poetry. “Letitia Elizabeth Landon.” Poetry Foundation, 12 Mar. 2021, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/letitia-elizabeth-landon.

Grey, O. (2022, April 26). The invention of the guillotine and its role in the French reign of terror. explorethearchive.com. https://explorethearchive.com/invention-of-the-guillotine

Landon, Letitia. “The Head .” The Keepsake, Longman, Rees, Greene, Brown, Ormes, and Longman, 1834, www.google.com/books/edition/The_Keepsake/74dRAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Matoff, Susan. “Landon Visits Paris.” Victorianweb.org, July 2020, victorianweb.org/authors/landon/lel7.html. Accessed 12 May 2024.

Miller, Lucasta. L. E. L. : The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron.” New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

White, E. (2018, April 6). The bloody family history of the guillotine. The Paris Review. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/04/06/the-bloody-family-history-of-the-guillotine/

License

The text of “The Head” is in the public domain.

All editorial material by Sydney Smith is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- Little affairs of the heart, dalliances↩︎

- Tiffs↩︎

- Woman of spirit↩︎

- By the grace of god, I’m a spirited woman – and I know it↩︎

- Orchestra seats beneath the balcony↩︎

- The beautiful (or lovely) countess↩︎

- A bedroom or Private sitting room↩︎

- Literally Mr. Count, the narrator might be making fun of Amalie’s husband. This would be the equivalent of saying “his royal highness”, but in a sarcastic tone.↩︎

- This is a biblical reference to the Book of Daniel Chapter 6. Comparing something to the law of Medes and Persians means that it is immutable↩︎

- Stubbornness↩︎

- The wretched (people)↩︎

- Originally, a royal prison where the king sent his enemies. The bastille was historically overthrown during the beginning of the revolution in 1789, representing the people opposing the king’s “god given” authority↩︎

- sorry↩︎

- A wife like few others or a wife like no other↩︎

- Her close friend, AMIE is in the feminine her so we could also translate as girlfriend↩︎

- Party, but it is important to note that the modern spelling is a bit different, so could mean something a little different↩︎

- Could be a reference to Marly-la-Ville, to the northwest of Paris. Important to note that there are other Marly’s in France↩︎

- Marie Antoinette became the queen of France in 1774 when her husband, Louis XVI took the throne. She was later dethroned during the French revolution and executed under the guillotine in 1792. She is most known for saying “Let them eat cake” after hearing that the peasants didn’t have enough bread to eat.↩︎

- Her lovely (beautiful) Amalie↩︎

- Cute, adorable↩︎

- Literally our good man, probably referring specifically to Louis XVI, who most likely would have been king at the time↩︎

- Literally, a knot of ribbon, but could also be translated as a ribbon bow↩︎

- The lovely↩︎

- Traitor, devious, deceitful one↩︎

- This poor dear↩︎

- Spicy, hot. In this scenario could just mean more interesting or scandalous↩︎

- A supporter of democracy and antisocial/misanthropic↩︎

- Commoner↩︎

- Unwilling permission↩︎

- A conceited, foolish person↩︎

- Chevalier means knight, but there is no clear translation for l’Escars. l’Escars could be a place↩︎

- Too early↩︎

- philosopher↩︎

- A bigot or sanctimonious person↩︎

- The lovely eyes↩︎

- In the ancient style↩︎

- a gem carved in relief:↩︎

- Armchair, easy chair↩︎

- admirer↩︎

- The Jacobins were a political group during the French revolution, that believed in extreme violence and egalitarianism. They were the primary political power in the National convention from 1793-1794, also known as the reign of terror:↩︎

- Propriety or decorum↩︎

- Using Monsieur represents a return to formality, as if they were strangers.↩︎

- One must respect propriety↩︎

- Conceited and tyrannical↩︎

- The guillotine was frequently used for executions during the French revolution, specifically during the reign of terror (1793-1794). Guillotine executions were often very theatrical.↩︎