Edition created by E. Liang

Table of contents

“No; I do not want to vote—not yet… I fear it might be taken for granted that I have no ideas of my own and might be counted upon to walk up like a sheep.” So begins the simple but strong speech by Marian, the main female character in “The Twenty-One Club” by May McHenry. Written over 100 years ago, this short story addresses topics relevant in the present, from informed voting to voter suppression. The title club, The Twenty-One Club, becomes an example of powerful change when the norm is challenged.

Editor’s Note

Every year, there are elections that change the government on local, state, and national levels. The year is 2024, and another presidential election is just months away in the United States. Recently, it seems like these elections have divided the nation more and more. According to the United States Census Bureau, voter turnout has increased in the past decade; however, still, less than 70% of the eligible population votes.1 The lack of informed voting and voter suppression prevent a greater participation of voters that would be truly reflective of the beliefs and goals of this nation.

“The Twenty-One Club” by May McHenry was published on July 6, 1899 in Volume 51 of The Independent. The magazine was published weekly in New York City from 1848 to 1928. The first three editors were all Congregational ministers who focused on Congregationalism and abolition. Congregationalism was a Christian movement that emphasized the autonomy of each congregation. In 1861, the editor changed to Henry Ward Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, and the magazine began to focus on women’s suffrage as well. In the late 19th century, the magazine tended to focus less on religion and more on politics.

This short story addresses topics of gender roles of the time, women’s suffrage, and informed voting. A large cast of characters are introduced. A speech given by the main female character, Marian, inspires the action of her male family members to start a club dedicated to becoming more informed voters, therefore better citizens.

I chose to digitize this short story for many reasons. In general, there is much value in stories that have not been republished, therefore a risk of losing them. Through reading this story, and a variety of other stories in class, I have developed a deeper appreciation for short stories, especially those that are less popular. These less-known stories provide unique perspectives, not only reflective of the past but also relevant in the present.

Specifically, this story has continued relevance in modern academic, social, and political settings. In academic settings, this story falls under subjects such as American history, American politics, as well as Women and Gender Studies. In social and political settings, this story connects to the topics of informed voting and continued voter suppression.

According to the article, “The political consequences of uninformed voters” by Fowler and Margolis, informed voting is important in a democratic system for the government to reflect the values of its nation’s people. A lack of understanding of the policies of certain politicians or the true views of political parties can result in individuals voting against their actual beliefs. This issue disproportionately affects people in lower socioeconomic classes.2

Furthemore, the government is only able to reflect the voters in a nation; voter suppression affects various groups and prevents those groups from being well represented. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, for incarcerated people, depending on the state, their right to vote after being incarcerated ranges from never lost to lost indefinitely. Even though there is a wide range of possibilities, there is a general trend toward allowing incarcerated people to eventually regain the right to vote.3 Furthermore, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, for people of color, people with disabilities, and students, measures such as restricted registration, strict voter ID laws, and voter purges all create barriers that make it more difficult for people in these communities to have their voices heard.4

For this version of “The Twenty-One Club”, I remained true to the original diction and syntax. Footnotes throughout the story identify and clarify possibly unfamiliar words (definitions are taken from the Merriam-Webster dictionary); however, I noticed, overall, this story is still very readable in its original editing for modern audiences. In addition to the transcribed text, I have included a historical essay and a creative response. The historical essay dives deeper into education at the time and the women’s suffrage movement, which I identified as social and political influences on the writing and publication of this short story. The creative response presents visual interpretations of the story as well as prompts thought of alternative endings.

Enjoy,

E. Liang

“The Twenty-One Club” by May McHenry

On Old Man John Barton’s eightieth birthday there was a family reunion at The Homestead. The Bartons are numerous and clannish, consequently they gathered in strong force at the big, square white house on the site where their great-grandfather, John Barton, built the first log cabin north of the Wishshinky.

Family reunions are nothing uncommon with the Bartons, but there were features that distinguished this party from other affairs of the kind. For one thing, it was Old Man John’s first and last eightieth birthday. Then all the John Bartons were present. John is a good, solid, sensible name, and the Bartons rather like it; there is Old Man John, and John Junior, and John third, and Little John, and Johnny K., and Danville John, and John the Blacksmith, not to mention John Barton Todd and young Johnny K. Barton Morton. But the great distinguishing feature of the party was the founding of the Twenty-One Club.

Old Man John was interested and moved when he counted up and found there were nine young men of the Barton family who would attain their majority before the year was out.

It was at the time of the Easter vacation, and all of the nine happened to be at The Homestead birthday party. They were gathered into the big parlor—three young farmers, a Harvard junior, a medical student, a law student, a musician, a telegraph operator and a drug clerk—all trying to look dignified and unconscious5 as grandfathers, uncles, cousins slapped them on the back and called them fine young roosters,6 and joked about beardless cheeks and mustaches like the down of a half-fledged pigeon.7

“Nine new votes for the straight Democratic ticket!” said John Junior, who was a member of the State Legislature. “That ought to turn the scale in Christopher County next fall.”

“I tell you, it makes the old man’s heart big with pride to see so many fine young shoots around the parent tree.” said Old Man John in his loud, hearty tones. “The older generation is nothing but half-dead branches hanging on until a gust of wind snaps them off; and it is a comfort to know there is plenty of sound, sappy, heart-whole Barton timber coming on—good American timber, too, the sort the Government needs for props.” Old Man John had been a lumberman in his day, so he used a lumberman’s figures.

They were talking in that way, guying,8 flattering and applauding the foolish-looking young men, when a pretty, brown-haired girl stood beside Old Man John’s chair, her eyes bright and saucy.

“I, too, will be twenty-one soon, grand-father,” she cried gayly.9 “Next Fourth of July, the nation’s birthday. Why do you not call me a promising young sapling?—a birth sapling?”

The old man squeezed the plump little hand of the merry young schoolma’am,10 his favorite grandchild, and told her she was a moss rose, a honeysuckle and a rare white lily.11 The boys, relieved to find themselves no longer the center of interest, laughed teasingly and told their cousins she was only a girl and had better pass herself off as a minor as long as she could—her coming of age announced to nothing, for she would have no vote any way; she could never be an American sovereign and help rule ninety millions of people through the ballot box, the glory and the pride and the sacred responsibility of citizenship were not for her.

Pretty Marian, secure in the admiration and loyal allegiance due her as the only young lady in a family burdened with so many bothersome and ungainly12 young males, did not mind the laughter and teasing in the least. But when the misguided Harvard student adopted a patronizing tone and hinted that she was a New Woman13 and intended to assert her equality at the polls as well as in the matter of birthdays, Marian stood up very straight, with slight flush on her cheeks.

“No; I do not want to vote—not yet,” she said calmly. “I fear it might be taken for granted that I have no ideas of my own and might be counted upon to walk up like a sheep and vote the straight Democratic ticket just because the Bartons usually belong to that party.”

“No,” she went on, without noticing the laughter and applause, “I could not consider myself fitted for the glory and the pride and the sacred responsibility of citizenship while I boasted a better acquaintance with the formation of the ancient Greek republics than with the Constitution and political history of the United States.”

The Harvard man fell back and drew in his breath sharply as a sign that he had been hit; but the little school teacher went on undisturbed, and it was the good-looking drug clerk who clapped his hand to his heart at her next shot.

“Being only a girl, I would lack courage to assume a share in the government of ninety million people when I have never even looked at the instrument forming the basis of that government, the Constitution of the United States. If I was likely to become a voter I might consider my duty to inform myself about some of the national questions and the attitudes of the parties, and about political methods. At any rate, I feel sure I would read something in the newspapers besides the baseball news, and in addition to being able to give biographies of all the crack players of the league teams I would know the names and the places of the members of the President’s Cabinet; also I would find out whether or not the unit rule14 has anything to do with the way a Speaker of the House runs things.”

“Why, do you know,” and she threw back her head like her father, the Judge, when he gave a charge to the jury—“Why, do you know, if I had the prospect ahead of me of having a vote in the management of my country, if I, like you boys, should have the rights and the power of an American voter when I reach twenty-one, I would accept the responsibility with the spirit of the Czar of Russia receiving his crown on his knees, with tears running down his face; I would do as the knights of old did before they took the solemn vows of their knighthood: I would go off alone and strengthen my soul by fasting and prayer. That is what I would do if I was going to vote next fall!”

There was such a roar of applause and laughter that Marian darted out of the room in sudden confusion. The next minute the dining-room doors were thrown open and they all flocked out laughing and talking noisily—all except Marian: she disappeared into the kitchen and stayed there the greater part of the afternoon, making herself useful.

After dinner some of the boys met on the porch.

“Marian rather pitched15 into us, didn’t she?” remarked Will Barton.

“The baseball and Cabinet members’ stab was meant for me,” announced Will’s twin brother, Dan. “Wonder who was tripped up on the unit rule?”

The musician, who was dangling his long legs over the railing and gazing dreamily at the hills, turned without a word and screwed up his face into such an irresistibly funny wink that the others shouted with laughter, and Johnny K. and the Harvard man hurried up to join in the fun.

“I dare say it would not hurt any of us to know more about such things,” the Harvard man observed thoughtfully. “I for one will admit that I ought to be better informed as to the duties and privileges of American citizenship.”

They all appreciated the astonishing modesty of Jimmie in making such an admission, and showed their appreciation by agreeing with him promptly.

Then Johnny K. straightened himself up and threw away his cigar.

“Why do not you fellows do something?” he said. “There are nine of you who will vote for the first time next fall, and sixty or seventy others, possibly, throughout the country. While acquiring a little information yourselves you might influence some of the others to take a more intelligent interest in the Institutions of the country. You know the theory: the higher the intelligence and virtue of the average voter the nearer we approach the ideal republic.16 Why don’t you do something for your country to celebrate your coming of age?”

Now Jonny K., a rising young lawyer, lately elected district-attorney, a keen sportsman and a good fellow, was the admiration and secretly cherished model of all the boys, especially his younger brother, the Harvard man; consequently his suggestion carried.

That evening Marian walked home through the fields with her cousins, Dan and Will.

“Well, we’re going to do it,” Dan began.

“Do what?”

“The Czar of Russia receiving his crown, the knight taking his vows act. Only we will have an American, modernized version: fasting might not agree with the fragile, up-to-date constitution. Behold in me the treasurer of the Twenty-One Club!” and he rattled the silver in his pockets.

“Yes, we have formed a club,” Will explained. “Object, to study the Constitution of the United States and—er—to prepare ourselves for citizenship. We intend to take in as many fellows who come of age this year as we can get to join us. The club will buy books and papers for circulation among the members.”

“Jimmie is president because he knows parliamentary rules and how they do such things at Harvard,” Dan interrupted. “John third is secretary, and Johnny K. is legal adviser. Johnny K. is out by age and cannot be a regular member, and he seemed to feel he had been born too soon. I tell you he’s great, Johnny K. is. He said you deserved a medal for stirring us up the way you did.”

“Oh, he was not in the room. He could not hear me. Oh, I hope not!” exclaimed Marian in distress. “I made a great fool of myself. I hope he did not hear me!”

“I don’t know. We told him all you said and more,” Dan said consolingly, as he opened the gate for her.

“Oh, by the way, Marian, you’re a member of the Twenty-One Club by acclamation17—at Johnny K.’s suggestion,” Will called after her as she passed up the walk.

The club thus formed ran a quiet and uneventful course for some months. The nine original members were scattered at their various places of work and study, but many new members were added, letters were exchanged, and the books, pamphlets and newspapers of the club “course” were in lively demand.

It was not until the latter part of June that people in general began to hear much of the Twenty-One Club. Then it was known that Christopher County was to have a big Fourth of July celebration at Bomtown, the country seat, and that a number of young men “comin’ twenty-one” had been invited by the mayor and the committee to be present as guest of honor.

But the interest and excitement stirred up by the preparations for the celebration was felt throughout the whole country. It was known that the famous Ringgold Band from the State capital was to be present at the expense of a single citizen—Old Man John Barton. The announcement that the young men of the Twenty-One Club would be treated to a free dinner aroused much comment and curiosity. Then the list of the speakers’ names fairly took away the breath of the farmer who had read in his weekly paper for years of the brilliant and witty Congressman M—, of the magnetic and forceful Senator K—, without expecting to have a chance to hear them.

When the great day came to the pretty park at the edge of the town was filled to overflowing with gayly expectant town people and country folks and mountaineers, all animated and half deafened by the patriotically emulative18 strains of the Ringgold and other less famous but equally ambitious bands. On the flag-draped speakers’ stand the local luminaries19 were almost lost from sight in the exceeding brilliancy of an ex-Governor, a United States Senator, a member of Congress, and an ex-candidate for Vice-President. In front of the stand, dividing public interest with great men, sat a group of forty or fifty youths—the Twenty-One Club.

When each noted speaker had had his turn and had been cheered until the trees shook, then the Twenty-One Club rose to its feet as one man and with all the breath it had left lifted up such a mighty shout as made the previous din seem tame.

“Johnny K. Barton! Johnny—K.—Barton!” was what they yelled.

Now the young district-attorney, knowing the Twenty-One Club, had a few well chosen words, a few happy phrases, ready for just such an emergency. As he swung himself up on the platform and stood there in front of those distinguished men who had long been the objects of his critical admiration, and felt that their surprised, questioning eyes were boring holes through his shoulder blades, all those graceful words, all that fine rhetoric20 floated off and left him for one hideous moment feeling that the universe was a vacuum.

Then he saw the eager, expectant faces of the boys and another eager, expectant face further off under a big white hat, and he knew he did not need the escaped thistledown21 rhetoric. The occasion, the waiting audience, the inspiring thought of immense results that might spring from words of his presented to those young men who believed in and were so thoroughly in sympathy with him, was preparation enough.

There are some members of the Twenty-One Club who will never forget certain words be uttered: and the memory of those words and of that one day on the threshold of manhood gives added value and meaning to manhood itself and to patriotism.

The young men were not alone in considering their club a success. It was not only the approbation22 of the distinguished visitors but als the enthusiastic support of the general public. Before the day of celebration was over a new club, or rather a new chapter of the club, was organized by youths who would reach their majority during the following year. Thus the Twenty-One Club promises to become a permanent institution in Christopher County.

Marian rode home from the celebration in Johnny K.’s buggy. They took the long way round, as Jonny K. liked to do when he had his pretty second cousin beside him, and the sagacious23 mare chose her own gait. Consequently they were the last to arrive of the returning party.

As they approached the house in the sultry, dusty dusk, Marian saw a group of dark figures beside the gate.

“Those awful boys!” she exclaimed, and started in confusion to draw her glove over something that sparkled on her left hand.

Johnny K. stopped her. “They will never notice,” he said. “And what if they do?”

The nine Barton boys formed in lines on each side of the walk and waited in solemn silence as Marian advanced toward them doubtingly. Then President Jimmie stepped forward rather awkwardly for a Harvard man and handed her a huge bouquet of lilies and moss roses. He made a little speech in which Marian caught the words “birthday,” “cousins” and “Twenty-One Club.”

She began to thank them prettily, but Jimmie interrupted her. “There is a case attached to the stems,” he explained.

Further speech was prevented by the whirr and whizz and bang of a sudden discharge of fireworks. By the scintillations24 of the pinwheels and the red, green and yellow light of rockets, Marian opened the little leather case and saw a novel and beautiful brooch, in the form of an American eagle in gold bearing a small enameled flag in his talons. On the accompanying card she read:

“To a New Woman; from nine voters.”

The little school teacher turned as tho she would like to hug somebody, and the nine voters retired precipitately.25

“We had a notion to give you a diamond ring, only we knew Johnny K. wanted to do that himself,” the irrepressible Dan told her.

Marian laughed and blushed.

“Boys, the nation and I have had such a beautiful birthday!” she said.

Historical Essay

While the original text was quite readable and understandable as is, after finishing the story, I found myself curious about more of the historical context and how it may have influenced the author. Going into the short story, I was generally familiar with the women’s suffrage movement; however, I wanted to specifically focus on the years leading up to the publication of this story. I also looked into the time after because I felt the story had a forward perspective that was important to consider, especially because the story did not necessarily go in the direction I expected, that is, explicitly suggesting women should gain the right to vote.

The late 19th century was a time of much change in the United States, marked by the Civil War, the Gilded Age, growth of education, industrialization, westward expansion, the women’s suffrage movement, and more. Growth of education and the women’s suffrage movement are especially relevant to the short story, “The Twenty-One Club” by May McHenry. This story was published in July 1899 in New York City by the periodical The Independent. While little is known about the author, the time period around which this story was published can be analyzed to determine possible social and political influences.

Throughout the 19th century, education in the United States became more widespread and standardized. According to the Center on Education Policy, previously, education was limited based on factors such as gender, location, race, and socioeconomic status. Beginning in the 1830s, the idea of public schools became more popular. These schools would be funded by the public, accessible to all children, and teach a variety of subjects with the purpose of better preparing children for being productive members of society. While these schools were meant to connect children of various backgrounds, there was still notable discrimination against females and children of color.26

The influence of the growth of education can be seen in various aspects in “The Twenty-One Club.” Much of the beginning of the story is the female main character, Marian, giving a speech that inspires her male family members to start a club with the purpose of becoming more informed voters, therefore better citizens. They grow the club to include as many men of their age and fund the purchase of different materials. This development parallels the development of education in the United States with the general purpose of being more accessible. Another connection is Marian’s acknowledgement of her, and other women’s, lack of education. This reflects how while education was becoming more accessible, it still discriminated against women.

According to “The Women’s Suffrage Movement,” The Seneca Falls convention in 1848 in New York can be most clearly identified as the beginning of the national women’s suffrage movement in the United States. At this convention, the Declaration of Sentiments, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was presented, describing the rights of women which had been denied, wrongs of the political structure in place at the time, and ways to resolve these issues. Between the Seneca Falls convention and the couple of decades leading up to the publication of this short story, the women’s suffrage movement continued to face many barriers and challenges; however, following the emancipation of enslaved people, the movement tended to grow.

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage (ASWA) Association were both major organizations involved in the women’s suffrage movement during the 1880s. The 1884 election included the Equal Rights Party which nominated Belva Lockwood for president and Marietta Stow for vice president. While her campaign was divisive, she did secure some votes, and it was mainly successful in increasing press on the women’s suffrage movement. The next decade began with the unexpected merger of the NWSA and the AWSA into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), with Elizabeth Stanton as president. After a couple of years, Elizabeth Stanton was succeeded by Susan B. Anthony. While a variety of issues arose with the new NAWSA, they were able to achieve many successes as well in the 1890s. This new organization marked a major split between the women’s suffrage movement and the civil rights movement, with women suffrage becoming more closely associated with White supremacy, especially in the South.27

In the early 20th century, after the publication of “The Twenty-One Club”, the women’s suffrage movement continued to grow. According to the article, “National Woman’s Party Protests During World War I,” throughout 1917, women associated with the National Woman’s Party picketed the White House, holding up signs to pressure the president and government into passing the 19th amendment.28 Through harsh weather, violence, and arrest, these women continued to show up and protest. Their active protests against the government contrasted NAWSA, when in April 1917, when the United States became involved in World War Ⅰ, supported the government to reflect their commitment to the nation. Women in the United States finally gained the right to vote in August 1920 when the 19th amendment was ratified, stating citizens cannot be denied the right to vote on the basis of sex.29

The influence of the women’s suffrage movement can be seen in various aspects in “The Twenty-One Club.” I think an opinionated main female character is progressive for a time in which women were often seen as submissive. This strength is taken further as her speech causes the males in her family to change, showing they are flawed characters which goes against the typical dominance and relative perfection of men. They even positively acknowledged her as “a New Woman” in the end. In the beginning, this nickname was used in a condescending way, yet by the end, it was used in an appreciative way.

However, I think it is interesting to note how the author tends to take a more moderate view on women’s suffrage; the story never explicitly states women should gain the right to vote. Instead, the story seems to criticize the lack of informed voting. In doing so, it seems the emphasis on who should vote is less men versus women and more informed versus less informed. I think this approach makes the story more attractive to a variety of audiences, especially at the time it was published. While the author could not have predicted it, I think it is interesting how this main focus, informed voting, is still an issue today.

Furthermore, it is interesting to analyze the character space of this story. With Marian’s speech being such an important part of the story, specifically at the beginning, I expected her to have more of a presence throughout the story. Instead, there seems to be a shift to focus more on the Twenty-One Club. Even with her speech, it seemed like less of a characterization of herself and more of the men in her life. Yet, Marian is still developed to be a complete character with a distinct personality and strong beliefs. This choice contributes to the author’s more moderate view because there is a fairly even divide between Marian and the large cast of men, allowing various readers to identify with different characters in this story.

Another author choice I noticed is the lack of reference to other tangential social and political focuses, such as race, religion, and temperance. Once again, this choice may have been in part due to the desire to appeal to a larger audience. I also think it is important to think geographically. While I am unsure where the author originates, this story was published in New York City. About thirty years after the end of the Civil War, there were still many differences between the North and the South. The lack of mention of race and religion could possibly reflect the less emphasis in the North and the lack of ties to the author; in other words, the author may not have been involved in the tangential anti-slavery and civil rights movements as well as she may not have been strongly religious. This moderate approach is similar to the approach of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, in general, making the story more accessible to and even more enjoyable for a larger audience.

Overall, since I was not able to find more information about the author—“The Twenty-One Club” appears to be May McHenry’s only published work—I had to speculate about the many possible social and political influences on this short story. I identified the growth of education and the women’s suffrage movement during the 19th century as main contributors. I analyzed key events in both to connect them to the story. In doing so, I noticed similarities between the growth of education with the author’s message of the importance of informed voting, seemingly more so than sex, socioeconomic status, or race. I also believe that the time in the women’s suffrage movement, in which the movement was still growing and split between different beliefs, relates to the seemingly more moderate approach the author has to suggesting women should be able to vote.

Creative Response

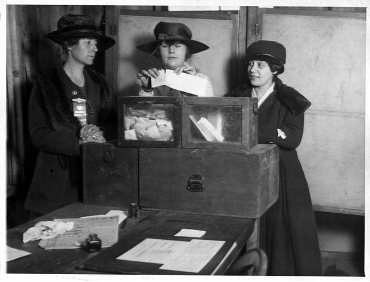

Through this creative response, one of my goals was to incorporate various representations of women’s suffrage from around the time of publication of this short story. First, I collected photographs and posters related to this topic. Next, I looked for similarities and common themes within and between these different forms of media. The photographs are all black and white. To me, this represents more of the struggle of women’s suffrage. On the other hand, the posters incorporated color. To me, this represents more of the hope of women’s suffrage. Specifically, the common use of yellow gives a more positive and happy perspective. In both, the use of bold text is not only noticeable but also gives strength and a sense of confidence to the movement.

Furthermore, this story did not have the satisfactory ending that I was hoping for. While Marian positively impacted these men by making them more informed voters, she herself still lacked that right. For the time it was published, about two decades before women in the United States gained the right to vote, such an ending may have been too radical. However, more realistically, while the men seemed appreciative of her in the end, I wish the author dived more into how the men seemingly supported Marian as “a New Woman.” Because of this, another one of my goals was to represent possible alternative endings to this story.

This set of images feature a solid background of a black and white photograph to represent women before the right to vote over which I used a transparent yellow-filtered photograph to represent women after the right to vote.

Original Images:

Merged Image:

Description 1:

The black and white image30 in the first picture is from 1920 and features women casting their vote in New York. The image in color31 in the first picture is from 2021 and features women casting their vote in Utah. I chose these images because I think they are very similar, even though they were taken about 100 years apart. However, a notable difference is the diversity of women in the second image which reflects even more progress since the first picture.

Original Images:

Merged Image:

Description 2:

The black and white image32 in the second picture is from 1888 and features the meeting of female suffragists in Washington D.C. Well-known individuals in the photo include Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. The image in color33 in the second picture is from 2013 and features the female Democratic members of the House. I chose these images because they show the progress made in the past 150 years. The women in the first image were just trying to get the right to vote while the women in the second image are participating, powerful members of the government.

License

The text of “The Twenty-One Club” is in the public domain.

All editorial material by E. Liang is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/2020-presidential-election-voting-report.html ↩︎

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379413001522 ↩︎

- https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/felon-voting-rights ↩︎

- https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/ensure-every-american-can-vote/vote-suppression ↩︎

- Unconscious — free from self-awareness ↩︎

- “fine young roosters” — well-behaved young men ↩︎

- “like the down of a half-fledged pigeon” — still developing, indicative of youth ↩︎

- Guying — to make fun of ↩︎

- Gayly — in a quick and spirited manner ↩︎

- Schoolma’am — a woman who teaches in a school in a small town or in the country ↩︎

- “a moss rose, a honeysuckle and a rare white lily” — nicknames of affection, possibly meaning love, happiness, and purity ↩︎

- Ungainly — hard to handle ↩︎

- “a New Woman” — an independent woman with skills comparable to a man ↩︎

- “the unit rule” — a rule under which a delegation to a national political convention casts its entire vote as a unit as determined by a majority vote ↩︎

- Pitched — to present especially in a high-pressure way ↩︎

- “the ideal republic” — an idea, described by Plato, that connects a just government to a happy nation ↩︎

- Acclamation — a loud eager expression of assent ↩︎

- Emulative — ambitious ↩︎

- Luminary — a person of prominence or brilliant achievement ↩︎

- Rhetoric — skill in the effective use of speech ↩︎

- Thistledown — the typically light pappus from the ripe flower head of a thistle ↩︎

- Approbation — an act of approving formally ↩︎

- Sagacious — having or showing deep understanding and intelligent application of knowledge↩︎

- Scintillations — a spark or flash ↩︎

- Precipitately — to bring about especially abruptly ↩︎

- https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606970.pdf ↩︎

- The Women’s Suffrage Movement (Penguin Classics) ↩︎

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/national-womans-party-protests-world-war-i.htm ↩︎

- https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/19th-amendment ↩︎

- Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (digital file no. 00037) ↩︎

- https://www.usu.edu/today/story/utah-women-decreased-in-rate-of-voting-but-civic-engagement-remains-high ↩︎

- https://www.history.com/news/early-womens-rights-movement-beyond-suffrage ↩︎

- https://www.glamour.com/story/photo-of-the-day-nancy-pelosi ↩︎