The Kinetoscope of Time

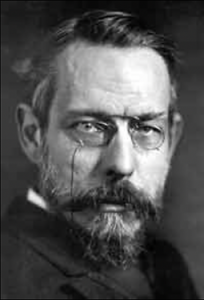

About the Author: Brander Matthews

by Jacqueline M.

Note: Information about Brander Matthews was found in multiple sources, mainly Columbia University Libraries’ Archival Collections and Matthews’ own autobiography. All information from external sources is hyperlinked in the following text, and a complete source list is located at the bottom of the page.

Early Life and Education

James Brander Matthews, often referred to as Brander Matthews, was born February 21st 1852 in New Orleans, Louisiana into a wealthy family.[1] In his autobiography Matthews describes frequently moving during his early years, often staying in Louisiana, Chicago, or traveling Europe with his family.[2]

Matthews’ states that he “became a New Yorker when [he] was seven years old” when his family moved to a house on 5th Avenue.[2] He attended boarding school in New York before attending Columbia University, where he was a member of the Delta Psi fraternity and the Philolexian society, the latter of which being one of the oldest student literary and debate groups in the United States.[3],[4] Matthews graduated in 1871 before pursuing his interest in debate by attending Columbia Law School, which he graduated from in 1873.[5] However, Matthew never practiced law, and his career would instead be focused on his other passion, literature. The following year Matthews earned a Master’s of Arts in Literature, also from Columbia University.[1]

Links to Kinetoscope of Time: In the Kinetoscope of Time there are various references to other literary works. Matthews’ use of intertextuality may be a reflection of his upbringing, education, and knowledge of literature.

Writing Career

Beginning in the years following his graduation from Columbia University, Brander Matthews’ writing career took shape. Plays such as A Gold Mine (1887) and On Probation (1889) –written by Matthews in collaboration with George H. Jessop– gained recognition for the young author, including features in the New York Times.[6] Matthews continued to write, and his works are over forty plays, essays, poetry collections, novels, and biographies,, including his own autobiography titled These Many Years: Recollections of a New Yorker.[5]

Aside from his own works of fiction, Matthews wrote collections of scholarly essays on the art of playwriting and playmaking, historical novels, and American literature. His writing was also featured in periodicals such as Scribner’s Magazine, The Nation, and Harper’s Monthly.[7], [1] Matthews’ works gained recognition internationally, too, and the French government awarded Matthews a Legion of Honor for his research and writings on French literature and theater in 1907.[1]

Links to Kinetoscope of Time: The Kinetoscope of Time was first published in the 1895 July-December issue of Scribner’s Magazine. [8]

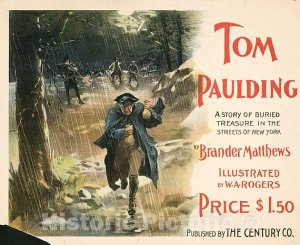

Despite his birth in Louisiana and a variety of travels throughout his early life, Matthews considered himself to be a New Yorker, as the city was where he spent most of his life. New York was clearly important to Matthews, and the city was the setting in multiple of his books such as Tom Paulding: the story of a search for buried treasure in the streets of New York (1892), Vignettes of Manhattan (1894), and Vistas of New York (1912). [1]

Links to Kinetoscope of Time: The narrator of Kinetoscope of Time describes the setting as a city. Given Matthews’ love of New York and previous use of the city as the setting for many of his other works, we can wonder if it was Matthews’ intention that the city in the Kinetoscope of Time is another reference to New York. It’s clear that living in New York affected Matthews’ writing and serving as inspiration, thus we may consider how Matthews’ own history contributed to the settings of or subjects of his works…

Teaching and Professorship

Brander Matthews began giving lectures in the Columbia University English department in 1892, and eight years later became the first Professor of Dramatic Literature in the United States at Columbia University. [1]

Matthews held his professorship until 1924, teaching the course Modern Drama, which still exists today in Columbia’s curriculum. [1]

Professional Affiliations and Literary Community Connections

Matthews was deeply invested in fostering a community of authors in New York and was a member of many literary groups throughout his lifetime, including The American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Grolier Club.[1] He was additionally a founder of The Players’ Club and The Authors’ club, and he additionally helped form the American Copyright League.[1]

Personal Life

In 1873, the same year he graduated from Columbia Law School, Brander Matthews married English Actress Ada Smith, with whom he had a daughter.[1]

Throughout his career Brander Matthews had friendships with multiple notable American figures in literature and politics, the most well known being Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States, whom Matthews dedicated his 1894 book Vignettes of Manhattan to.[9]

In 1922 Matthews’ daughter passed away, and two years later in 1924 Matthews resigned his professorship following the death of his wife. Despite his professorship ending, Matthews continued to lecture and write until he passed away on March 31st, 1929 at the age of seventy five.[1]

A Brief History of the Kinetoscope:

Note: Information about the kinetoscope was sourced from the Encyclopedia Britannica and Library of Congress. All information from external sources is hyperlinked in the following text, and a complete source list is located at the bottom of the page.

In 1891, Thomas Edison patented the kinetoscope, a new way to view moving pictures in which an individual could watch a film by looking through a lens at the top of the device.[12]

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “In [the kinetoscope], a strip of film was passed rapidly between a lens and an electric light bulb while the viewer peered through a peephole. Behind the peephole was a spinning wheel with a narrow slit that acted as a shutter, permitting a momentary view of each of the 46 frames passing in front of the shutter every second”. [13]

As stated by the Library of Congress’ page on the kinetoscope, the name “kinetoscope” came from the combination of two Greek words. The page states, “Edison called the invention a “Kinetoscope,” using the Greek words ‘kineto’ meaning ‘movement’ and ‘scopos’ meaning ‘to watch’”.[12]

Reflections and Notes on the Research Experience:

When I first read The Kinetoscope of Time I did not know anything about Brander Matthews, nor did I know anything about kinetoscopes. Learning more about both of their respective histories gave me a much better understanding of the content and narrative style of The Kinetoscope of Time.

One recurring theme in 21L.003 has been the influence of an author’s personal life on their writing, which I kept in mind when researching and rereading The Kinetoscope of Time. In the case of Brander Matthews, there are a few explicit connections to his life in his writing, perhaps most noticeably his love of New York, which is featured as the setting for many of Matthews’ works.

The Kinetoscope of Time is written in a style that may perhaps also reflect Matthews’ life experience. Though my own knowledge of Matthews’ writing is limited to Kinetoscope and parts of his autobiography, it seems flowery, poetic language is characteristic of his works. After learning about Matthews’ education and lifelong dedication to literature I wonder if this aspect of his writing was adopted from or inspired by the classic literature he would have been exposed to as he developed his own writing style. This is, of course, speculation, but it is nonetheless interesting to consider how my own knowledge of an author affects how I view and understand their writing.

Another interesting result of my research was the realization of Matthews’ references to other works. At first I did not make the connection to other works of literature, which was perhaps due to myself not reading thoroughly on my first attempt, but while researching I found analysis of The Kinetoscope of Time in the introduction to Helen Groth’s book, Moving Images: Nineteenth-Century Reading and Screen Practices. While summarizing the short story Groth writes,

… [the narrator] looks through the eye piece and views a series of dance sequences from familiar historical and literary sources: Salome, Esmerelda’s dances from Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Pearl dancing before her cursed mother Hester in Nathaniel Hawthone’s A Scarlet Letter and Topsy dancing from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin the end of this sequence the narrator looks up, then follows another mysterious legend to a second kinetoscope where he views a sequence of military scenes drawn from fiction and history: the fight between Hector and Achilles, the tale of Saladin and the Knight of the Leopard from Sir Walter Scott’s The Talisman , Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Goethe’s Faust and Custer’s Last Stand… [14]

Matthews’ use of intertextuality reminded me of a few recurrent ideas from class. We have largely discussed the relationship between works of literature, and in particular, Groth’s comments made me consider Michel Foucault’s essay, What is an Author, in which Foucault questions his own inclusions of authors when analyzing literary texts, and discusses the relationship between an author and their works.[15] Though Matthews’ does not mention the authors of the stories he references scenes from, and the references are part of a fictional work as opposed to a scholarly one, I considered many questions Foucault posed when reflecting on his references to literary works, including the question of the function and desired effect of including specific scenes from well known pieces of literature such as The Scarlet Letter and Don Quixote. The purpose of the inclusion of these references, at least to my understanding, relates to the plot of the short story, as well as the historical context surrounding the kinetoscope.

As mentioned in the above “ A Brief History of the Kinetoscope” section, the kinetoscope was first patented in 1891, just four years before The Kinetoscope of Time was first published. The kinetoscope was a relatively new technology, and the idea of being able to see moving pictures as a source of entertainment or information must have been something many never thought possible. Perhaps the inclusion of the scenes from other literary works that the narrator sees through the kinetoscope relates to the way this new technology could be used to “see the past” in a new way. Stories that were old and already known could be experienced in a whole new format, suddenly made new again by technology.

Source List:

[1] Columbia University Libraries Archival Collections: https://findingaids.library.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-rb/ldpd_4078376

[2] These Many Years: Recollections of a New Yorker – Brander Matthews: https://books.google.com/books?id=6M4EAAAAYAAJ&

[3] Greek Letter Men of Washington, page 7: https://archive.org/details/greeklettermenof01maxw/

[4] Philolexian Society Wikipedia Page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philolexian_Society

[5] Columbia University, C250 Celebrates Columbians Ahead of their Time: https://c250.columbia.edu/c250_celebrates/remarkable_columbians/brander_matthews.html

[6] New York Times- Amusements Section 11/20/1890: https://www.nytimes.com/1890/11/20/archives/amusements.html

[7] Theodore Roosevelt, Brander Matthews, and the Campaign for Literary Americanism-Lawrence J. Oliver: https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.mit.edu/stable/2713194?origin=crossref

[8] Scribner’s Magazine, v.18 Jul-Dec 1895, page 732: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015015393286&view=1up&seq=835

[9] The Project Gutenberg EBook of Vignettes of Manhattan; Outlines in Local Color, by Brander Matthews: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38918/38918-h/38918-h.htm

[10] Brander Matthews Wikipedia Page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brander_Matthews

[11] Vintage Poster for Brander Matthews’ Tom Paulding: https://www.historicpictoric.com/products/historic-poster-tom-paulding-brander-matthews

[12] Kinetoscope Library of Congress Page: https://www.loc.gov/static/collections/edison-company-motion-pictures-and-sound-recordings/articles-and-essays/history-of-edison-motion-pictures/origins-of-motion-pictures.html

[13] Kinetoscope Encyclopedia Britannica Page: https://www.britannica.com/technology/Kinetoscope

[14] Introduction: Moving Images: Nineteenth-Century Reading and Screen Practices- Helen Groth: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt5hh2d7.6

[15] Michel Foucault, What is an Author?: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/pluginfile.php/624849/mod_resource/content/1/a840_1_michel_foucault.pdf

[16] Lomography Magazine: Thomas Edison and the Kinetoscope: https://www.lomography.com/magazine/112686-thomas-edison-and-the-kinetoscope